Editor-in-Chief, Alex Taylor, meets Danny Robins in his dressing room (with a spooky flickering light) before his Birmingham show to discuss all things Uncanny.

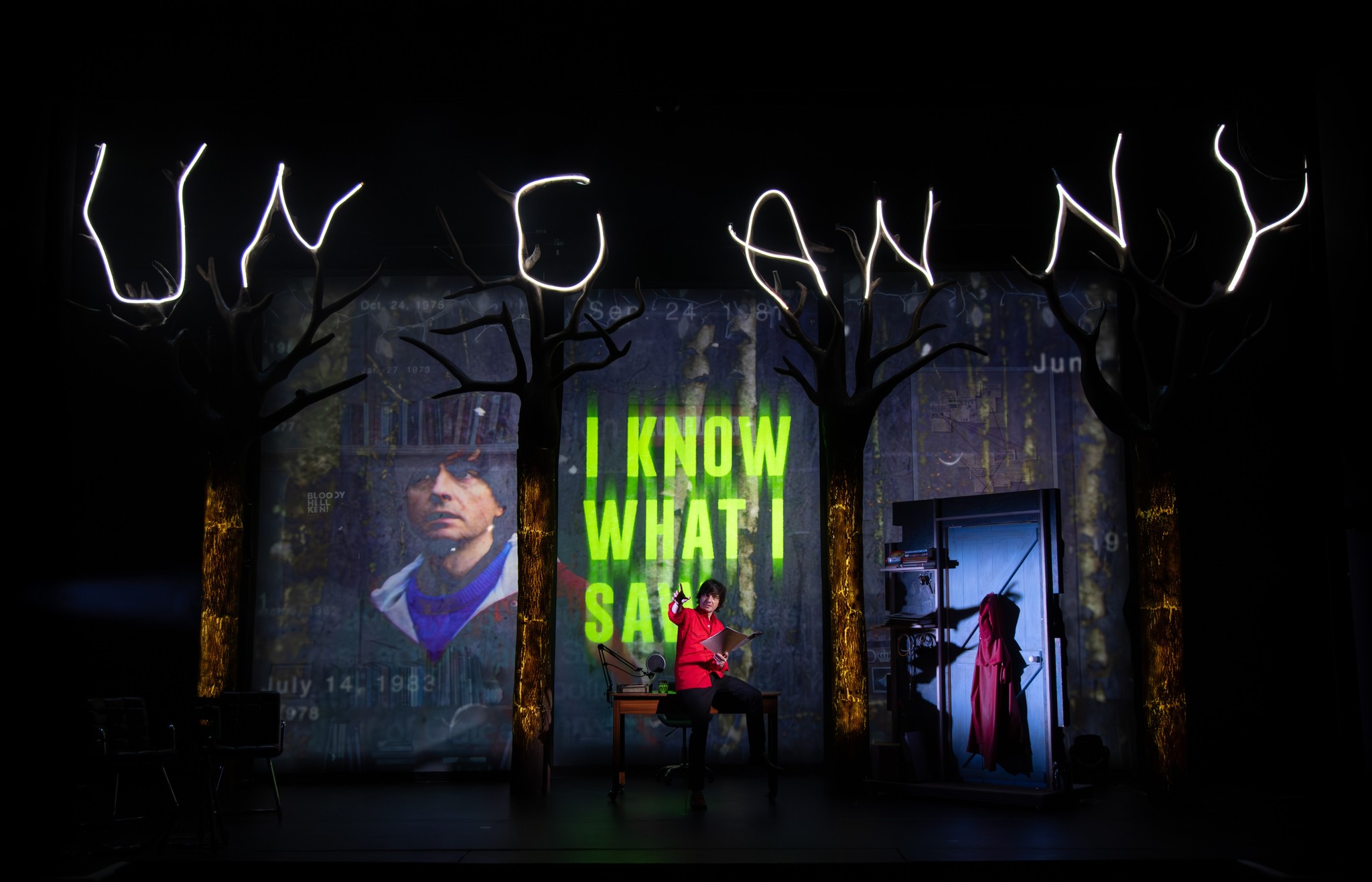

The live show ‘Uncanny: I Know What I Saw’, based on the international podcast phenomenon, Uncanny, that has sparked a BBC series, book, and sell-out live tour. At the helm of it all, the red parka adorning ‘go-to ghost guy’, Danny Robins. Of The Battersea Poltergeist, The Witch Farm, and 2:22 A Ghost Story fame, Danny, and his reliable team of returning experts return to the stage in what is the undeniably the biggest investigation into the paranormal ever conducted.

After being lead through the dark, rabbit-warren corridors beneath the historic Birmingham Hippodrome theatre, I was relieved to see the welcome-face of Danny Robins. As his dressing-room light flickered, and he tucked into his Chinese takeaway (of which he was unnecessarily deeply apologetic for), I had the absolute privilege of interviewing him before his show.

For our readers that might be slightly less familiar with your work, are you able to summarise your prior accolades that’ve led to developing such an international, devoted fanbase, as Britain’s ‘go-to ghost guy’?

I think its grown really, the first series I did was called Haunted, that was back in 2016. That sprung out of research for my play 2:22 A Ghost Story, and I’d had this idea after a friend of mine spoke to me and told me she’d seen a ghost. I remember thinking that our friends would react to her in very different ways: some people would be irritated by her talking about ‘this rubbish’, some people would mock her, and some people would question her mental health even; and some people would believe her. And I thought ‘wow, this is a real spectrum of responses that this moment would engender. What if you put that into a couple?’ So, I wrote this play about a couple, Jenny and Sam, where Jenny believes there’s a ghost in the house and Sam does not. Then there’s this consequent, explosive, Molotov cocktail effect on their relationship.

What I realised very quickly was that there wasn’t one type of person who sees a ghost

As part of researching that, I asked on social media if anyone else I know had had an experience, then I started getting these amazing stories in and they were from people who I thought ‘you’re not the kind of person who I would’ve expected to have seen a ghost’ and what I realised very quickly was that there wasn’t one type of person who sees a ghost, and those stories became Haunted, then Haunted gave birth to The Battersea Poltergeist. Then, Uncanny grew from that. I think that Uncanny has just specifically touched a nerve, really, there’s clearly a lot of people around the world keeping these experiences to themselves, not knowing how to talk about it, or who to tell. I guess, Uncanny provides a safe space to talk about it.

How would you describe Uncanny to someone who had never listened before, because it is quite a unique brand that you’ve created? Because, of course, it’s so much more than a podcast now, it’s a live show, a TV show on BBC…

And a book! I think it is quite unique hopefully. I think prior to Uncanny, pretty much all paranormal broadcasting divided you into two definitive camps, you were either very much preaching to the converted: we’ve all seen those programmes on telly, very much night vision cameras, screaming and celebrities running around haunted houses and mediums who channel spirits just in time for the commercial break; all that kind of thing. Then on the other side, you had really interesting people like Derren Brown, Richard Wiseman and Chris French: doing their scepticism and debunking these things. I felt there wasn’t a middle ground that brought those two camps together. So, one of the innovations was that thing of having a believer and a sceptic there as these two rival pundits. I was making the show that I wanted to listen to.

Do you have your own favourite cases, what would you say could also be the best episode for someone to jump in the deep end at?

I think the great thing about Uncanny is that we see ourselves reflected in it. You hear people just like you, who are having experiences unlike anything you’ve ever experienced before. That’s why it’s scary, I think.

For me, the one that sticks in my head the most is one of the most modest in many ways. It’s called ‘My Best Friend’s Ghost’, and it’s about a woman who lost her friend to cancer. She felt she saw her friend again as an apparition in a park. But, then years later after she’d consigned all that, she went to see a medium – thought they were completely rubbish and didn’t believe them at all – but then the medium stopped her after the show and said, ‘I just wanted to quickly tell you something, they didn’t want me to say it on stage’. The medium then repeats the exact dying words of her friend to her, which are really specific, niche and involved a nickname that only she could’ve known.

I feel like the experiences we’ve had for Uncanny: USA have been very Uncanny; these stories just feel to me like they have a different accent

Your new series of Uncanny takes place in America. How does that differ taking it stateside, besides the fact that so many stories involve a gun!

There are certain sort of things I could trot out to you about the difference between Americans Brits. Brits live in older houses, so we’re more likely to experience benign hauntings of people that used to live in our house. American hauntings seem to, generally if you look at American paranormal TV, be based more around violence and trauma, murders, serial-killers, asylums and penitentiaries. But I would say that those are stereotypes, and what I found is that Americans and Brits don’t differ that much, and we share experiences and a desire to make sense of them. I feel like the experiences we’ve had for Uncanny: USA have been very Uncanny; these stories just feel to me like they have a different accent. They still reign from the pure terror of people watching dark figures run at them seemingly intent on killing them, to moving subjects such as a woman making contact with her father from potentially across the grave.

What really sets Uncanny apart is that you don’t try to push an ideology on anyone. It’s not like you’re trying to convince anyone that there’s goblins under the stairs, and at the same time you’re not invalidating what are really personal experiences. Was that empathy intentional going into it?

Yes, absolutely. It’s how I feel, basically. I don’t think it’s a calculated intentional thing it’s just the way I would approach this subject and these people. I’ve always been fascinated by people, full stop. I love meeting interesting people, and I love hearing about strange moments in their lives and I guess that is the fuel of documentaries, the motor of any good documentary is about an interesting person.

We don’t have much tolerance for people making mistakes or for people being able to change

For me there is a semi-ideological thing here where I feel we have a real problem in society with division and forcing people into different camps. Also, in not allowing people to change their minds. We tend to hear something that somebody says, disagree with it, then forever judge that person by that statement or belief. We don’t have much tolerance for people making mistakes or for people being able to change. I think we need that. If you don’t allow for that possibility of people changing their minds, then what hope is there? Social media has become a trench warfare, you dig your trench and stick to your guns and define yourself by what you hate as much as what you love. Here in ghosts, I found something where you can create a world where people can agree to disagree. If you can have sceptics and believers coming together and having totally polarising opinions about what happens when we die, I feel like maybe we can do that about other things, maybe we could do that about politics?

I just think it’s important that there’s something to be said for keeping an open mind and listening without judgement, and that’s what we do in the show. Its primarily about listening, really, and facilitating someone to tell their story. And the thing is about a ghost story, is that when you tell it, you want to engender fear in the listen because you were so frightened yourself. You want them to know how you felt. Because if they do that, then maybe they’ll realise how vivid it was for you. So, I think we help people to tell these stories, make it scary through sound effects, but fundamentally we’re just giving a person a platform to relive a moment and try to make sense of it. The thing I love about this is how it becomes a group endeavour, this community: the Uncanny Community, who join together to try and make sense of these things even if they’re really hardened sceptics, they absolutely do not judge these people or pour cold water on what they say.

Did the experience of putting this together differ from your smash hit play 2:22 A Ghost Story?

There’s a lot of overlap. I think I’ve learned a lot about how to scare people over the years. I’ve found myself working with Blumhouse, the Hollywood horror producers who made Get Out amongst other stuff, and they optioned Battersea Poltergeist. I found myself working over there in LA, and they have this guy called a ‘scare-doctor’, a guy they bring in when they need to scare things up. Hearing his theories about what scares us is really interesting; the psychology of fear. So, I do feel as though my work has probably got progressively scarier, The Witch Farm, which I made after The Battersea Poltergeist, was probably scarier. Uncanny is scary but it’s very interactive in a way that 2:22 A Ghost Story isn’t. There is a nice degree of interactivity where everyone is not just smiling politely and nodding, but its very different.

if you listen to Uncanny, or any of my work, you can see humour in it, and I think it’s necessary

This show [Uncanny: I Know What I Saw] is very interactive, we have our audience up asking questions, hearing stories from everyone too, and for me it channels what I started out doing, age 16 I started doing stand-up in the North-East in the pubs and the clubs in Newcastle where I grew up and around that area. I’m channelling that inner stand up with lots of years at the Edinburgh festival doing comedy shows, and in 2:22 A Ghost Story is a funny play and if you listen to Uncanny, or any of my work, you can see humour in it, and I think it’s necessary.

Would you ever consider making a film adaptation of any of your work, 2:22 A Ghost Story perhaps? Make a sequel, call it 2:22: 2.

Or 2:23 A Ghost Story! I’ve had lots of conversations about doing a movie, and I think it is something that we would like to do. I would like to write more for the screen, definitely, and Uncanny has really taken over my life in such an unexpected way. Last year, I wrote a book, made a TV series, made two podcast series, did a tour, and this year is shaping up in the same way. So, its hard because its such an exciting journey with Uncanny, as somebody who a few years ago was a jobbing writer feeling, to some degree, kind-of ignored, to being in a position where you have this lovely community of people, this big fanbase now, and people want to engage with your stuff. Playing to this lovely theatre here in Birmingham full of people feels magical, I keep pinching myself. I feel like I need to invest time in this journey, and nurture that thing that’s growing.

Enjoyed this interview? Check out these other interviews from Redbrick:

Comments