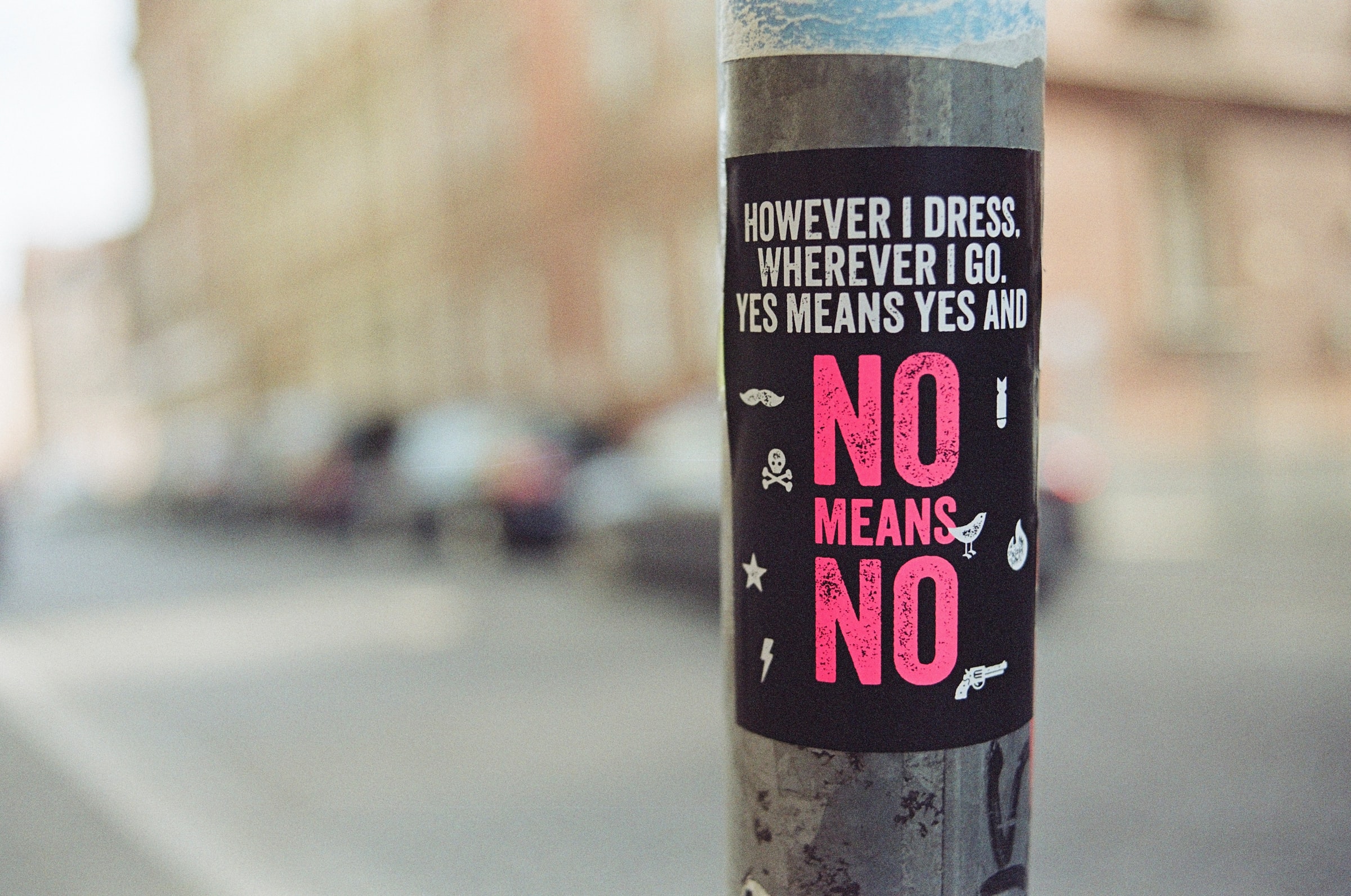

Comment Editor Esther Purves discusses the narrative surrounding sexual harassment and urges people to act against its trivialisation

Content Warning: Mention of sexual assault and harassment

‘But you weren’t really sexually harassed though.’

My male friend dismisses my story after I finish telling him about the harassment I experienced at work. There is a slightly awkward silence.

‘Look it up,’ I say. ‘That was sexual harassment.’

Using an official definition as a justification for my experience of sexual harassment is not unprecedented. My male counterparts have often struggled to accept my accounts of sexual harassment purely based on my word.

In their defence, the media rarely exemplifies a narrative that wholeheartedly supports or believes women who speak up about sexual harassment. Just last week, Jacob Rees-Mogg attempted to propose a bill that would allow the House of Commons to debate bullying or harassment claims made from parliament’s employees. Although the motion was rejected by parliament, the proposal from Rees-Mogg demonstrates the culture of criticising victims who complain of their sexual harassment. Furthermore, his position as leader of the house remains unquestioned. Men rarely seem to face significant consequences for refusing to take harassment seriously.

The media rarely exemplifies a narrative that wholeheartedly supports or believes women who speak up about sexual harassment

The endorsement of men who attempt to trivialise sexual assault is not unprecedented. Throughout his campaign for presidency in 2016, multiple women spoke out against Donald Trump’s assaultive behaviour. As women vocalised their allegations against Trump, his statements of misogyny were revealed. Despite these allegations, Trump was still elected into presidency. This election symbolised more than his popularity; it legitimised the trivialisation of sexual assault, subsequently creating a narrative that devalues allegations of sexual assault from women.

In light of these high-profile figures, I can understand why some of my male counterparts sometimes adopt the same trivialising attitude that they are shown in the media. It should also be noted that internalising these narratives is not exclusively a male problem. As women are surrounded by high profile male figures and their male friends, both of whom participate in attitudes that trivialise sexual assault, women also internalise those narratives. When I experience sexual harassment or assault firsthand, I start to question my own discomfort. Although I feel terrible, I start to question if my interpretation of the situation is accurate. Is it really this bad, or am I being dramatic?

After an incident with a guy on a night out, I called my mum. She asked me what I was going to do, and I told her that I was not going to do anything.

‘You’ve been sexually assaulted,’ she said. ‘You need to tell someone.’

I knew she was right. I knew I had been sexually assaulted. But I did not feel like I had been. I felt like I was a bit shaken up and that I needed to get over it. I had internalised every single narrative that I had been fed about sexual assault, and I left the situation alone. Men are never held accountable; women are often blamed for their own assault and my own university had hardly exemplified sufficient support for female students. The options for me were limited; deciding to trivialise my own assault was easier than facing an inevitable criticism of my claims.

When the culture of trivialisation is maintained by men in order to protect men, the prospect of seeking support is incredibly daunting. As narratives of criticism surrounding sexual assault survivors are upheld, it is difficult for women to feel safe and respected as they attempt to contend against their assaulters and harassers. In turn, women remain quiet, and subsequently, the harassing behaviour of many men continues to be accepted and unquestioned. This narrative is not just part of a culture, it is a self-perpetuating system that operates in the interest of protecting men.

The options for me were limited; deciding to trivialise my own assault was easier than facing an inevitable criticism of my claims

The perpetrators of this trivialisation appear to exist at a higher level than my peers. I do not believe this is the case. My male peers have the ability to challenge and disassemble the narrative surrounding sexual assault, merely by believing their female friends. They have the ability to create a space for women where their accounts of assault will be accepted. They have the ability to challenge what they know. Men are taught to trivialise and disbelieve the allegations of women; if she ever tells you of her harassment, be critical of your own response rather than her experience.

_______________________________________________________________________

Like this story? See below for more from Comment:

The Success of Female Leaders During Lockdown

Comments