Life & Style Editor Julia Lee reviews Riot Act, writing of the three monologues that comprise the play, taken from Alexis Gregory’s interviews with gay men who were queer activists

Content Warning: this article contains mentions of homophobia, transphobia, conversion therapy, police brutality, injury, and AIDS deaths which some readers may find distressing.

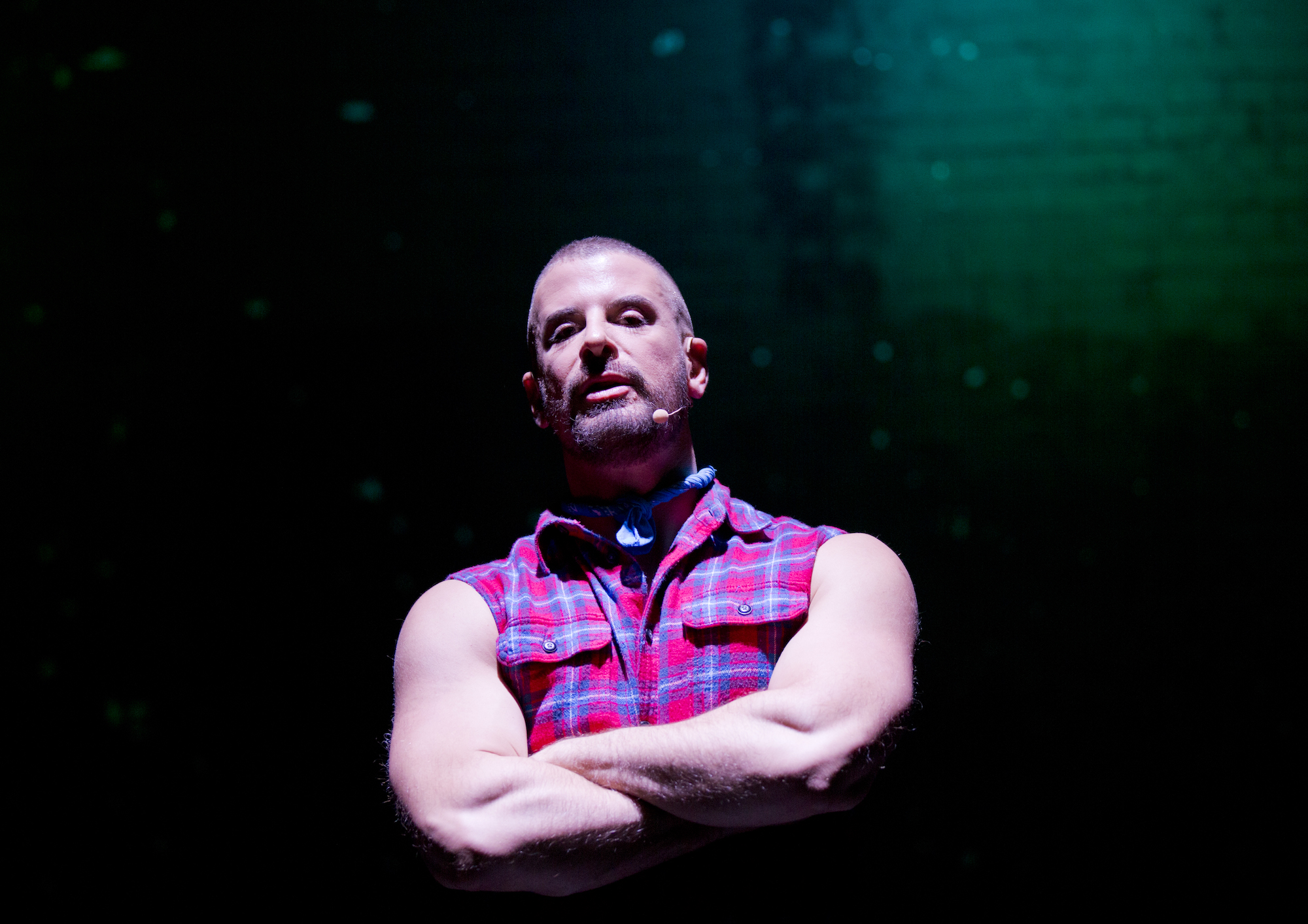

Alexis Gregory’s Riot Act was first staged in 2018 and is continually revised even today. Three monologues were extracted from Gregory’s interviews with three older gay men, who, by intention or mistake, became activists at a time when queerness was just becoming visible in mainstream consciousness.

The Black Box theatre at the Birmingham Rep is dark – the stage bare but for a chair under a coloured spotlight. This is ‘backstage’, the transitional realm where the actor becomes his character. We are first greeted by Michael to the dulcet tones of Judy Garland’s ‘Somewhere over the Rainbow’. He was seventeen during the 1969 Stonewall Riots, a small-town boy in a big city. From him, we learn of the different gay haunts near Christopher Street in Manhattan, with Stonewall Inn being the grimiest and most peripheral of them all. We learn about police raids – the elder gays and mature queens vulnerable to their brutality.

We learn that even amidst the chaos, there was no place like home

We see the only departure from the minimal staging – a white light that warned of an imminent raid, Michael abandoning the spotlight to press against the back wall. We learn not who ‘threw the first brick’, but Michael’s desperate attempts to deliver hot water to the injured so they could be cleaned up and sent to the hospital without attracting suspicion. We learn that even amidst the chaos, there was no place like home.

Lavinia, or Vincent, or Vin, comes alive to T-Rex’s ‘Children of the Revolution’. She is from Hackney, based for a time at a Notting Hill house share, and travelled the world. She is a radical drag performance artist. She tells us about finding her identity, attending Gay Lib meetings, and being visibly queer. She was both a mentee and continues to be a mentor (not just a legend). She remembers vividly the devastation of AIDS on her friends and community, believing only a memorial in the centre of London will suffice.

Paul is the youngest of the three and the most politically active. ‘Smalltown Boy’ by Bronski Beat fades out, and his story begins when he becomes aware of this ‘new disease’. He channelled his survivors’ guilt from his friends’ deaths and rage from institutional inaction into activism, joining the London branch of ACT UP, ‘AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power’. We learn from him all the loud and disruptive ways activists demanded attention from politicians and the press. He reflects on seeing so much positive change in so little time, that he is able to take his wedding photos on the bridge he chained himself to in protest just 17 years before. He warns of the importance of solidarity and the role lesbians and feminists played in Gay Lib that is often overlooked.

The monologues are unembellished but powerful in their simplicity, embodying the spirit behind verbatim theatre

The monologues are unembellished but powerful in their simplicity, embodying the spirit behind verbatim theatre. The interviewees speak directly to the audience, drawing you in, and each monologue ends with a tether to our reality, where an actor and playwright is broadcasting their stories to the world. We leave knowing their names, and the truth of queer history systemically barred from being taught in school.

Gregory, as Paul, bestows the audience with flyers stamped with ACT UP’s pink triangle and slogan ‘ACTION=LIFE’. We have heard from three queer elders about a time when direct action, riot acts if you will, was king. Gay marriage is not the end of the road for queer liberation, rather, it is as much placation as it is victory. It is said that ‘the price of liberty is constant vigilance’. The powers that be are fickle friends– if something is granted it can just as easily be taken away.

It was barely twenty years ago that the infamous section 28 that prohibited the ‘promotion of homosexuality’ was repealed. The fight for banning all forms of conversion therapy is ongoing, and in the United States more and more ‘don’t say gay’ bills are passed that threaten to upend any progress the movement has achieved. The gay rights movement has a short-term memory. When will we remember that acquiescing to the powers will only lead to the erosion of rights our queer elders fought for? But the gulf the AIDS crisis left is not unbridgeable, as long as we are willing to listen, and act.

Riot Act is on tour and will be available to stream online, details here.

Rating: 5/5

Enjoyed this? Read more on Redbrick Culture!

Theatre Review: The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time

Theatre Review: The Lion, The Witch & The Wardrobe

Theatre Review: Value Engineering: Scenes From The Grenfell Inquiry

Comments