Culture Writers Jasmine Sandhar and Eva Widdicombe reviews Sabrina Mahfouz’s adaptation of Noughts and Crosses and finds the production portrays the incessant doom and gloom of this apocalyptic abyss perfectly

Perspective One: Jasmine Sandhar

As someone who was an avid reader of Malorie Blackman’s best-selling young-adult series Noughts and Crosses, I could not help but immediately snatch up this opportunity to go see. Needless to say, I had fairly high expectations for Sabrina Mahfouz’s adaptation being shown at The Alexandra, but, unfortunately, not all of them were met.

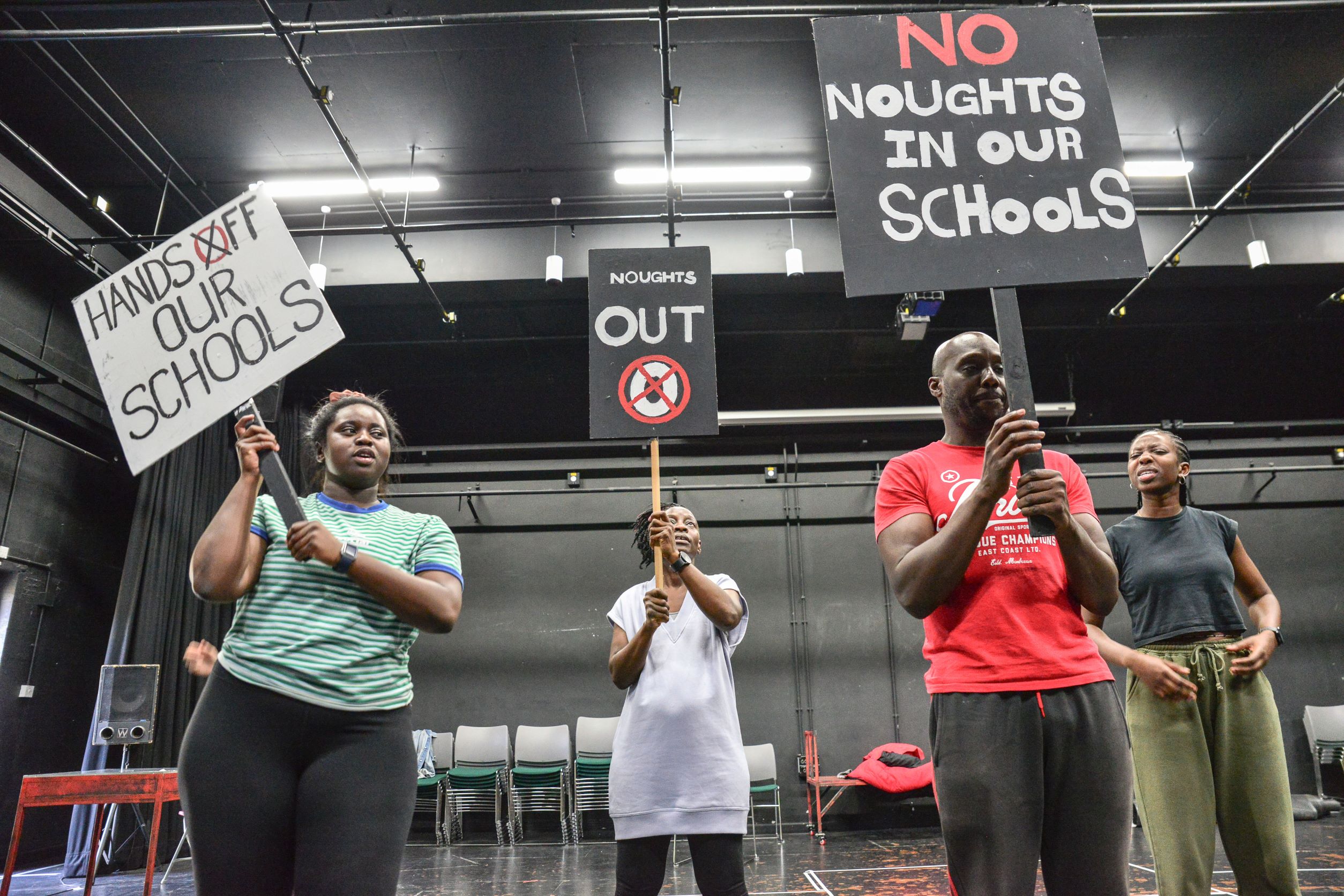

For those who are unaware of the plot, this tragedy is set in a dystopian future of the 22nd century, where – rather similar to the world of today – there is extremely deep-rooted racial inequality between the two race of the Noughts and the Crosses. The twist is that the “superior” race are the Crosses, who are darker-skinned people that embody the upper echelons of society, whilst the “inferior” race are the Noughts, who are lighter-skinned people that bear the brunt of lower-class impoverishment.

In this atmosphere of extreme animosity, two adolescents from either side of the divide do the unthinkable: fall in love. Persephone (a Cross) and Callum (a Nought) follow the classic Romeo and Juliet narrative, enduring the trials and tribulations of their forbidden romance against all odds. Without completely revealing all and giving away any spoilers, there is no happy ending at the end of this story.

“…the strongest part of the entire performance – the portrayal of the incessant doom and gloom of this apocalyptic abyss

I think this was perhaps the strongest part of the entire performance – the portrayal of the incessant doom and gloom of this apocalyptic abyss. The set perfectly captured the tension at all points, whether it was the intense neon red symbol glowing across the auditorium at the beginning, the unreliable television screens flicking between dismal news reports and monochrome static throughout, or the daunting steps leading up to a deadly noose at the end. This was accompanied well by the sounds of industrial-inspired electronic droning that blurred together to form waves of apprehension that washed over the audience.

In terms of the cast, the acting was slightly hit and miss. There were definitely some poignant moments where you could feel the more prominent emotions, such as rage and despondency – indeed, these scenes elicited some audible gasps from audience members, many of whom were actually schoolchildren – but at other times, it felt a little forced. For example, Persephone occasionally struggled to hit the right tone in certain interactions between herself and Callum, producing more of an amateur effect that perhaps was not intended.

“The set perfectly captured the tension at all points

Furthermore, the visible age gap between the actors playing these two protagonists probably did not help with their chemistry either, which failed to reach the heights of electricity needed. Although, I must say that there was a stirring energy in the air during the scene of sexual intimacy they shared in the unlikely context of a terrorist kidnapping.

To be frank, I do believe a lot of these issues stemmed from the scripting of the play. At times, the lines were a little cringe-inducing, and I think this could have been better avoided if there was a stronger connection between the novel and the play. If more sentences and specific words had been taken directly from the pages of Blackman’s book, the performance would certainly have been elevated to a plane that felt more realistic and immersive, rather than detached and disjointed.

“…the commitment of the cast is what caused a standing ovation from the audience at the end

Despite these hiccups, all in all, the production was an enjoyable experience. Whilst elements of the adpatation were not so well thought-out, the commitment of the cast is what caused a standing ovation from the audience at the end. The Alexandra’s choice to air a play so political in this current climate is also commendable.

Many parallels could be drawn between the Crosses’ maltreatment of the Noughts and this Conservative government’s response to the refugees seeking asylum in the UK from war-stricken countries. The message Blackman has managed to portray through this piece of art is timeless, and its significance must not be forgotten, as made abundantly clear in the theatre yesterday evening.

Rating: 3/5

Perspective Two: Eva Widdicombe

Last night, I saw Pilot Theatre’s production of Noughts and Crosses in The Alexandra, Birmingham. Having never read Malorie Blackman’s critically acclaimed 6 part series of books, yet being aware of the key concepts due to their success, I was intrigued to see how Blackman’s powerful coming of age novels were dramatized.

The play, set in speculative parallel world where black people (Crosses) have repressive power over white people (Noughts), follows the familiar trope of forbidden love, as Sephy, a cross, (Effie Ansah) and Callum (James Arden), a nought, navigate the transgression from childhood friends to secret lovers in a racially charged, hostile environment, a world set against their love’s success. It ends in tragedy.

Andsah and Arden play the lead roles with tender believability, Arden particularly triumphing in showing the steady erosion of an idealistic boy into a man hardened by the succession of injustice his family endures. Andsah portrays the naivety that comes with privilege well, and maintains a captivating energy throughout, yet personally I thought her performance appears too childlike in later parts of the play when she is a young woman, carrying a child.

“Andsah portrays the naivety that comes with privilege well, and maintains a captivating energy throughout

Steph Asamoah plays the role of Sephy’s sarcastic older sister Minerva brilliantly, and Nathaniel McCloskey, Daniel Copeland and Emma Keele, playing Callum’s brother, father and mother respectively, showed the struggles of being working class Noughts with incredible poignance, frustration, and strain – creating a perfectly tense and unforgiving atmosphere. Chris Jack, playing Effie’s father, a media mogul with enormous power, lacked the slickness and authority one would expect of his character, at times becoming stilted and awkward.

Poor script writing for Effie’s mother, Amie Buhari, left repeated references to her being an alcoholic becoming juvenile and joke-like, as we never saw her drunkenness come to life – a missed potential for what could have been incredibly poignant, distressing acting. Parts of the play where the central cast doubled up to play members of society, or part of the terrorist group, were confusing and unnecessary as clearly recognisable as key characters – it would have been far more effective if other actors fulfilled these roles.

The physical theatre sometimes left a lot to be desired, there were unnecessary moments of chair lifting for bomb explosions and rushing forwards to imitate the sea which felt amateur and unprofessional and didn’t fit with the realism of other scenes. However, the script was for the most part strong, scenes showing the tenderness of young love were juxtaposed with scenes of bullying and destruction, likewise intimate family moments were opposed with the grimness of the outside world, and cold, authoritative judicial scenes. Dramatic tension did escalate effectively, yet a little too slowly at first – the first half was too long, perhaps understandably though as there was a lot to cover. Some lines slightly missed the mark – monologues by Effie and Callum about ‘feeling like the sea’, whilst romantic, felt slightly GCSE- drama-esque.

“scenes showing the tenderness of young love were juxtaposed with scenes of bullying and destruction

However, the play was saved by the incredible set design by Simon Kenny, corrugated iron panels backlit with an ominous red, created the constant feeling of a dystopian world at war, and the panels were used effectively by characters to move off and on stage. A haunting moment was when Callum’s elder sister’s silhouette was shone behind the panels, we were told she never leaves her room, and this translated visually as being a prisoner behind bars. TV footage broadcasted onto the panels also worked fantastically. Lighting and sound was equally as impressive, the music throughout created constant unease and kept the play moving, helping the first act’s slow pace.

Despite the play undeniably being at a good level, there were no stand out moments where I ached at the unfairness of it all, nor angered at the injustice shown, nor moments which frightened me to distress, yet I did root for the central characters wholeheartedly, and on the whole, the play successfully left me pondering Marianne Blackman’s ethical, social and moral dilemmas long after I left the theatre. Whilst moments could have been improved, falling slightly below the level of powerful and emotive theatre I craved, I applaud Pilot Theatre’s admirable attempt.

Rating: 3/5

Enjoyed this? Read more Redbrick Culture here!

Theatre Review: Shawshank Redemption

Comments