TV Editor Josie Scott-Taylor considers the role of the ‘Bond Girl’ in the James Bond franchise, concluding that it is an outdated and misogynistic portrayal that should be seen through a critical lens

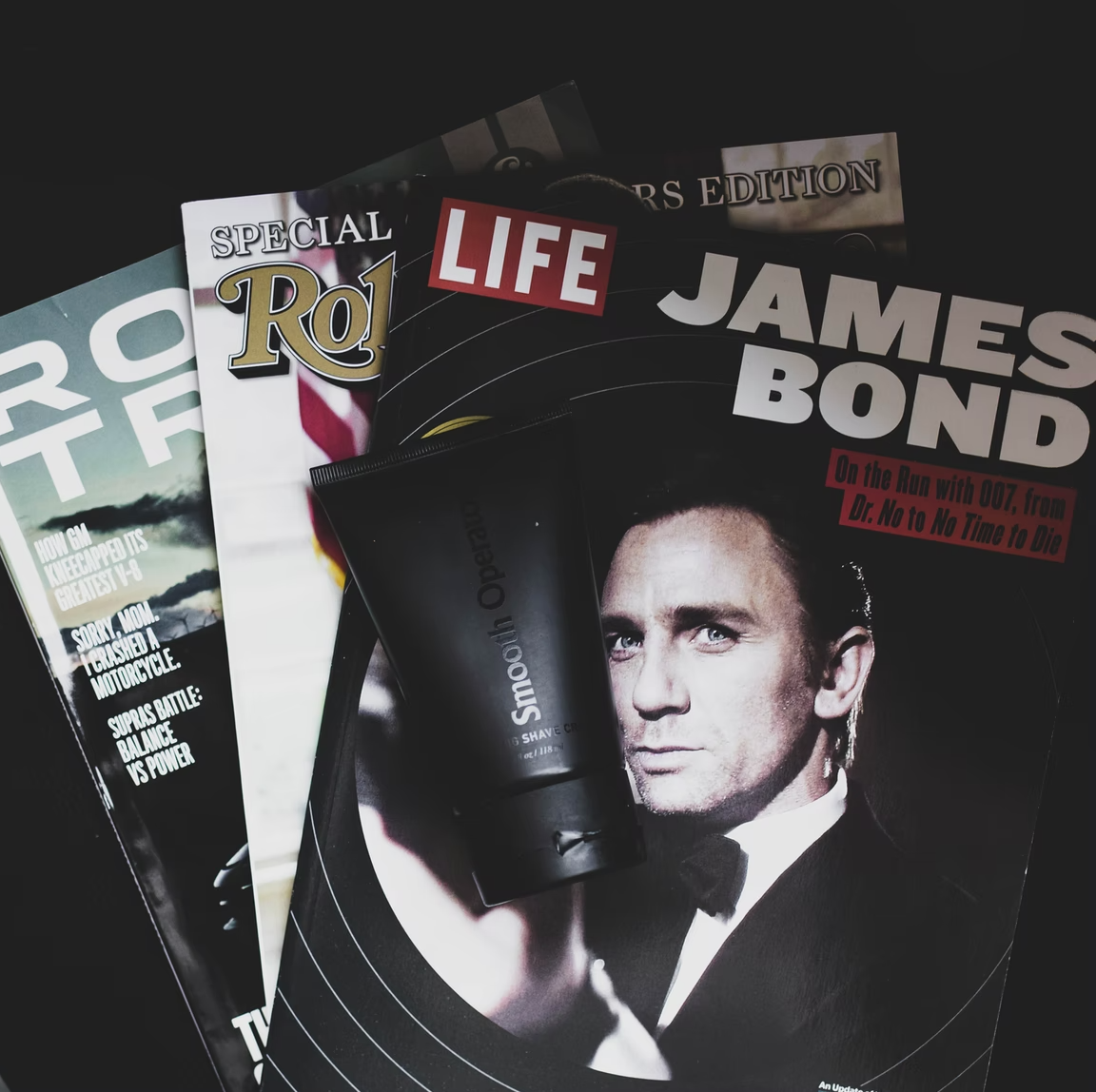

When someone mentions the name ‘James Bond,’ I can take a wild guess at the images and associations those two words conjure up. Vodka martinis (shaken, not stirred), suave, expensive suits, high-tech gear, and gorgeous women in revealing dresses. One aspect of the worshipped film franchise that people seem unwilling to focus on, though, is the rampant misogyny that runs throughout each instalment.

The insistent misogyny that pervades every instalment of the Bond franchise would be far easier to accept if his character was not sold as the embodiment of British charm, and as a role model for men

The ‘Bond Girl’ phenomenon is one that has sparked much controversy: is it sexist, or is the so-called ‘PC Brigade’ taking things too far? I am not here to argue that the entirety of the James Bond franchise is misogynistic, or that you should not watch the films. I am simply here to advocate for consuming media through a critical lens, rather than claiming that the forceful sexism of characters as revered as Bond is acceptable because the difference between fiction and real-life is obvious. Although this separation may be crystal clear to some of us, these step-by-step guides like ‘How To Be James Bond: Science Explains Why He’s Irresistible To Women’ and ‘The essential guide to being as cool as James Bond’, as well as songs like Scouting for Girls’ I Wish I Was James Bond prove that this distinction is not quite so apparent to some people. A short YouTube video titled ‘Inappropriate Moments in James Bond Movies’ demonstrates that perhaps being as ‘cool’ as Bond is not something to aspire towards. The insistent misogyny that pervades every instalment of the Bond franchise would be far easier to accept if his character was not sold as the embodiment of British charm, and as a role model for men.

The fact that so many female characters from so many different films are able to fit into just three concise categories highlights the lack of nuance and depth that the roles involve

Entertainment Weekly posits that there are three main categories that Bond Girls fall into: the sacrificial lamb, the femme fatale, and the hero. The fact that so many female characters from so many different films are able to fit into just three concise categories highlights the lack of nuance and depth that the roles involve. One of the least sexist examples of a Bond girl is Madeleine Swann (Léa Seydoux), a character who actually moves the plot forward rather than just acting as a plaything for Bond. Her character actually made history as the first Bond girl to have a significant role in more than one instalment of the franchise, and is not sexualised in the same way as many of the others, leading Seydoux to ‘gush’ over her character and the importance of her being seen as a ‘woman not a Bond girl.’ Seydoux’s excitement at the idea of not being objectified demonstrates the importance of writing roles for women that actually do something for the plot and are not filled with scenes that sexualise, rather than celebrate, the character. Just the infantilising nature of the title ‘Bond Girl’ is one that is ignored by too many people.

Although the franchise has certainly become more suited for the 21st century, with Bond seemingly developing more of a moral code than he possessed in the earlier films, the ‘Bond Girl’ concept remains an outdated one. Even No Time to Die director Cary Fukunaga admitted that Bond was ‘basically’ a rapist in an older film, referring to a scene in Sean Connery’s 1965 Thunderball where the ‘charming’ spy forcibly kisses a nurse after she has refused his advances, later promising to keep quiet about information that could potentially cost the nurse her job, so long as she sleeps with him. Fukunaga is far from innocent himself, having been recently accused of firing an actress for refusing to shoot a topless scene. Perhaps the evidence of sexism both on and behind the screen highlights the need to re-evaluate what James Bond really represents in the 21st century.

When people idolise James Bond and what he stands for, they are idolising a man who objectifies and mistreats women

When people idolise James Bond and what he stands for, they are idolising a man who objectifies and mistreats women. I am not saying that Bond is a villain whose existence needs to be eliminated from our society, but that as a society we should strive to watch films through a more critical lens. Until guides on ‘how to be like James Bond’ stop being written, or Bond stops being a misogynist, justifying the sexism in the films through the apparent distinction between fiction and reality is not an argument that holds up.

Read More from Life&Style:

The Political Runway: America’s Female Politicians

Overworked and Underrepresented: Why ‘Burn Out’ in Women Needs to Be Discussed

Comments