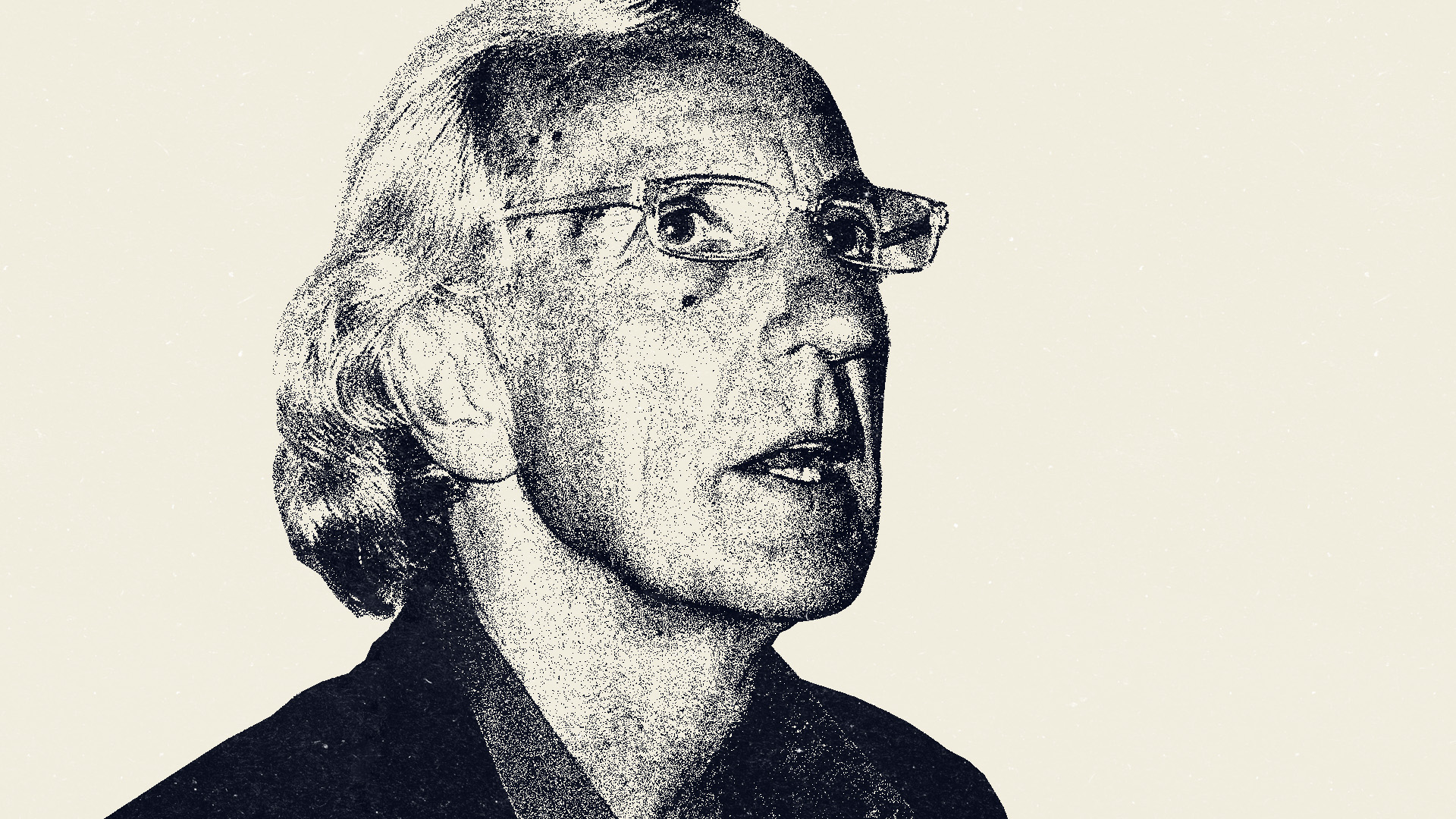

Film Editor Toby Jarvis comments on controversial documentary filmmaker John Pilger, whose work is being shown in a special BFI season

The Australian documentarian John Pilger, who died last December, has been posthumously celebrated with a season of his work at the BFI Southbank. The late Mr Pilger occupies a special place in popular imagination as a stalwart opponent of imperialists and tyrants everywhere—to quote the British Film Institute’s own description, ‘Pilger was called a ‘dangerous subversive’ for dissenting from the ‘official version’ of events’.

A recurring trope in the obituaries that poured in last year was that he was a journalist of rare principle, and this enabled him to reveal the unfettered truth on globally important events: the Vietnam War, the Cambodian Genocide, the War on Terror.

His work in Cambodia is a particular stand-out—the 1979 ITV documentary Year Zero, about the crimes of the Khmer Rouge, inspired an outpouring of humanitarian support from a newly aware British public. It would be impossible to argue that Pilger did not have a hand in the $45 million raised, and it is this episode for which he is most fondly remembered; Year Zero occupies a central place in the BFI schedule.

All this only makes the fact of the matter more difficult: that Pilger was not a universal enemy of the despot at all, but, given the right circumstances, one of their most fanatical cheerleaders.

This pattern of rhetoric—denial, obfuscation, justification—is something of a recurring theme

Retrospective commentary on his films published even while Pilger was alive has a bizarrely elegiac quality, which is owed to the awkward conversations discussing his later-life propagandism would invite. The Cambodia story I just gave is the most well known in a canon of 1970s parables about the power of documentary, which funnily enough is the name of the BFI season. Pilger’s early work is the founding tenet in the myth of him as maverick anti-authoritarian, and as such it receives by far the most attention.

Less mythologised is a distinctly unglamorous 2018 appearance on RT (or Russia Today, the state-owned news network now banned in this country) in which he bafflingly suggested a Russian chemical attack in Salisbury was a hoax: ‘a carefully constructed drama in which the media plays a role’.

Pilger was a regular on RT—the BBC’s diplomatic obituary notes that he ‘attracted controversy for his comments on Russia’, although it is probably more accurate to describe him as an outright pro-Russian commentator. After spending eight years justifying the seizure of the Crimea, he repeatedly insisted that a full-scale invasion of Ukraine would not take place; when, of course, it did, he changed tune and began explaining why it was a proportional reaction against Western imperialism.

This pattern of rhetoric—denial, obfuscation, justification—is something of a recurring theme in late career Pilger. Regardless of his own personal brand of Lubyanka leftism—rants about ‘the extreme provocation that a Nato-armed borderland presented to Moscow’ aside—it must be noted that he was very sympathetic to any nation adequately anti-American.

There is a litany of anecdotes about Pilger’s ability to reject inconvenient truths

Pilger’s ability to interrogate the official narrative seemed to decline catastrophically around his favourite officials. In an interview with the Venezuelan quasi-dictator Hugo Chávez, whose socialism had made him a target of American foreign policy, he fawns: “You are deeply committed to the Venezuelan people. Where does that come from?”. This wet flannel appeared in the documentary The War on Democracy (not running at the BFI), whose central thesis is that Dubya-era US intervention amounted to a form of neo-colonialism.

Questioning Chávez’s authoritarianism would make things difficult—it would stop him being a perfect victim of American empire—so Pilger decides not to acknowledge it at all, regardless of any responsibility as a journalist. A lot of his philosophy seemed to revolve around working backwards from a given conclusion.

There is a litany of these anecdotes about Pilger’s ability to selectively reject inconvenient truths—the slaughter of Kosovan Albanians under Slobodan Milošević, which he christened ‘a genocide that never was’, the atrocities of Assad in Syria (‘a complete propaganda construct’), and so on—but to preoccupy ourselves with such stories is to miss the wider trend they represent.

It is fitting that Pilger was so interested in war, whose first casualty is truth. To selectively condemn or deny a crime based on its perpetrator is the behaviour of a documentarian of allegiance, not principle.

Back to the BFI: why is it still entertaining this hagiography around John Pilger? I am not saying it should not show his work, or that none of it carries merit—to do so is the exact campism to which he dedicated the back half of his life—but surely it warrants slightly more critical examination than the blind praise of him as a champion of ‘hidden truths’.

For more Comment articles:

Do Patriarchal Structures Continue to Undermine Women’s Autonomy?

Comments