Film Writer Cameron Bowles assesses various leaders of the free world on screen, from romantics to Rambos

Land of the free, home of the brave, America has been a long-standing subject and setting for much of cinematic history, and simultaneously a constant focus for both national and global media. On November 6th, Donald Trump emerged victorious over the incumbent Democratic Party, setting him up to be the 47th President of the United States and returning him to the White House. Ali Abassi’s recent Trump biopic, The Apprentice (2024) shines a light on his earlier years but ends decades before his presidential bid(s). Considering this, it’s a better time to see how presidents have been represented on the big screen.

Our most acclaimed directors and performers have depicted some of the most lauded US presidents. Lincoln sees Steven Spielberg and Daniel Day-Lewis collaborate to present the last few months of Abraham Lincoln’s life as he attempts to end the American Civil War and pass the 13th amendment, abolishing slavery. Spielberg’s approach is restrained; he lets the drama speak for itself, allowing Day-Lewis and the remainder of the star-studded cast to monologue, debate and ultimately come to an agreement.

Oliver Stone’s presidential trilogy–JFK (1991), Nixon (1995), and W. (2008)–stand out for their controversial, even conspiratorial qualities. Stone is doubtlessly critical of the successive presidencies, whether it be engaging with the theories on who truly killed Kennedy or painting a complex, almost Shakespearean portrait of one of America’s most divisive presidents. The visuals of these films are best described as frenetic, replete with archival footage, dutch angles and historical recreations.

When real-life leaders fail to satisy, Hollywood turns to recognisable stars to take up the Oval Office

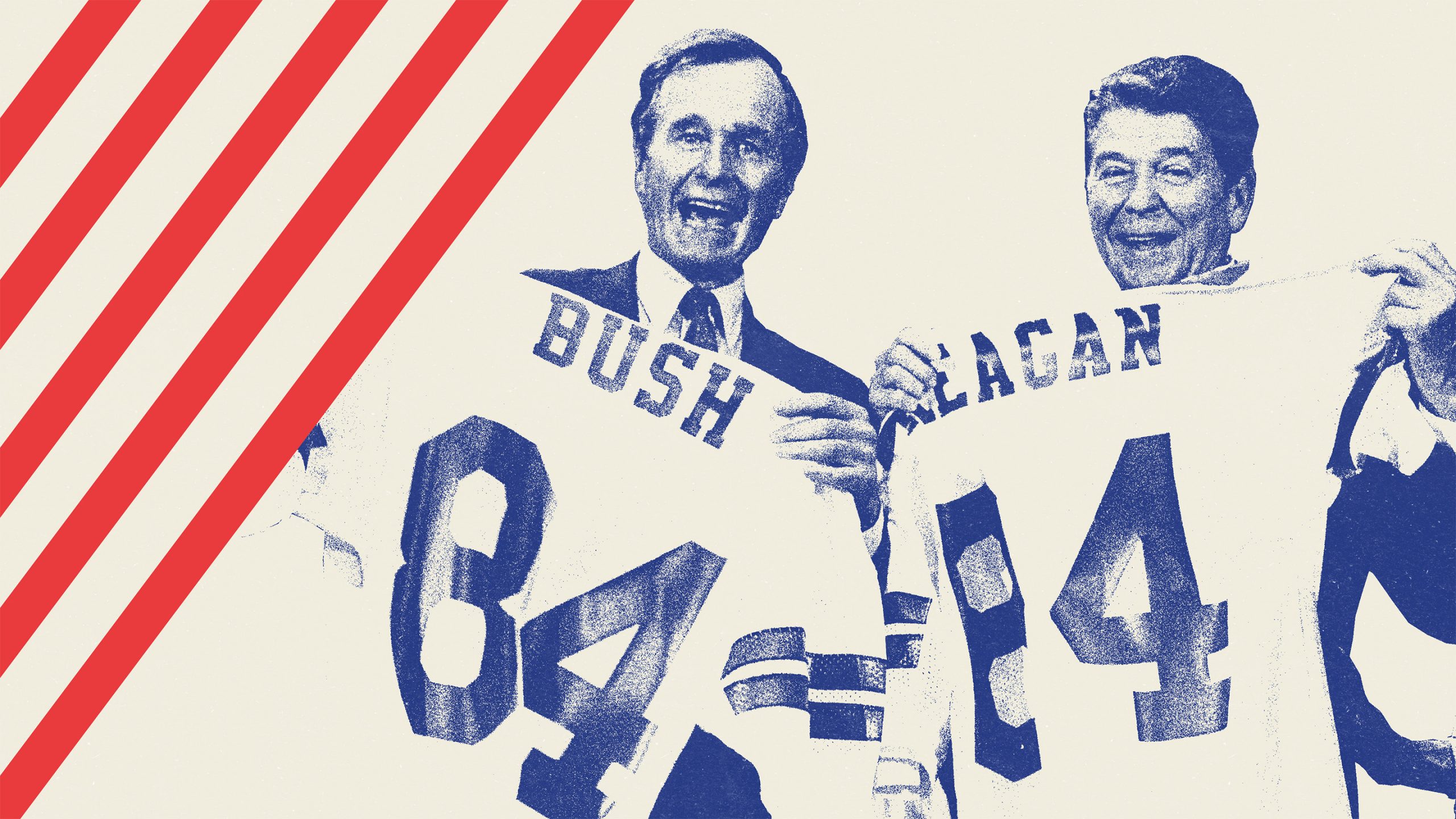

Lesser efforts have also come about, namely this year’s Reagan biopic in which Dennis Quaid gives a ham-fisted performance as actor-turned-politician Ronald Reagan. Far from utilising the complexity of this subject, paralleling the president’s star power and electoral popularity with his contentious policies at home and abroad, the movie opts for a one-note appraisal of the man. Other critics have described it in such glowing terms as “pure hagiography” and “a slog.”

While biopics and historical accounts tend to critically evaluate the tenure of a president, fiction allows for more idealist versions to be created. When real-life leaders fail to satisfy, Hollywood turns to recognisable stars to take up the Oval Office. Enter Harrison Ford in Air Force One (1997). Here, the president becomes an action hero, willing to take matters into his own hands when terrorists hijack his flight, duly throwing them off with the famous line “Get off my plane!” On the lighter side, Michael Douglas in The American President (1995) plays a charming rom-com lead, choosing a relationship over the party politics that overcrowds his life. Although less violent, this portrayal embodies the same essential features in its idealistic, saccharine view of the statesman.

Perhaps we yearn for a better president–one that is ultimately fictional

I believe that these versions provide the most interesting profiles in terms of how politics and entertainment intertwine. Ushering in a second Trump term, it’s imperative to recognise the contrast between reality and fiction–in both Democrats and Republicans–and know that these representations are often far from the truth. Real people are much messier, and real politicians are much less principled. Trump himself has often blurred the line through his film cameos and reality TV appearances. It begs the question, how far the presidential office has been mixed with pure entertainment; do people follow US politics out of a real material interest for it, or simply to be amused?

Perhaps we yearn for a better president–one free from scandal, corruption and controversy, one that is ultimately fictional, one that has not and will likely never exist. No matter your personal politics, we all feel an urge to glorify the leaders closest to our ideological and moral ideals. Film, in some way or another, has fulfilled that desire.

Read more News articles:

Richard Parker Rules Out Council Tax Increase Through Mayoral Precept

The Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery: A Beacon of Culture reopens after a four-year renovation

Comments