Film Critic Luke Pierce Powell reviews Emerald Fennell’s uneven satire

Entering Emerald Fennel’s latest film, Saltburn, I braced myself for a cinematic experience that had garnered both glowing praises and biting critiques from friends and family. BY the end of the runtime, the dichotomy was very apparent, and as the credits rolled after two and a half hours in the screening, I found myself toeing the line between infatuation and infuriation.

From the get-go, the film’s visuals demand attention. Each frame appears meticulously curated, with a heavy stylization that propels it off the screen The rapid cuts may sometimes deny us the chance to fully absorb the beauty, but the lingering shots provide a canvas to soak in the visual feast. The colour grading is particularly effective, transforming even the most repulsive scenes into a captivating struggle to look away. Despite the discomfort of the subject matter, the need to keep our eyes fixated on the screen ensures that no nuance is missed, at times blurring the line between a summer romance film and a social thriller.

Fennell has crafted a clever meta-commentary

Surprisingly, the film immediately acknowledges the concept of style over substance. Ollie, played by Barry Keoghan, is criticised for the focus on the subject of his essay and not the rhetoric. Similarly, Rosamund Pike’s Elsbeth state that she must only be around pretty people, and on multiple occasions reinforces that she has no care for the substance of people; who they are really. With this, Fennel has cleverly crafted a meta commentary that seamlessly intertwines the film’s visuals and characters, offering a glimpse into their worldview – how they view each other and the world around. Even in times of sheer pain and heartbreak, they each keep up appearances as best as they can for it is all that they have, and they do so under some of the best lighting and colour-grading of the year. However, this pretty and shallow facade crumbles when the camera zooms in for super close-ups, focusing solely on characters’ faces. In these moments, devoid of style, we glimpse substance—the true motives and cores of the characters.

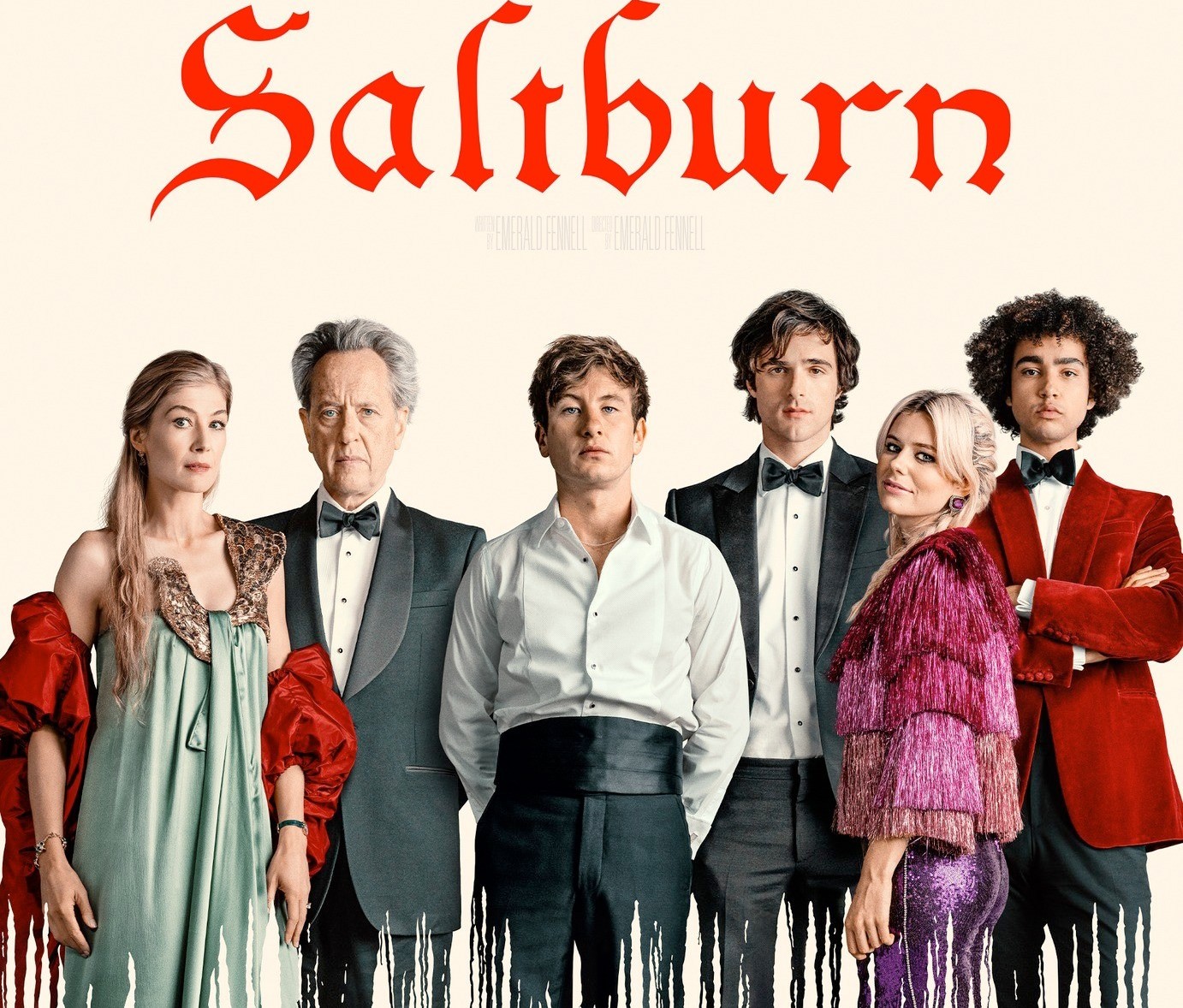

While the performances across the board are outstanding, with Keoghan, Elordi, Grant, and Pike delivering electrifying portrayals of the toxic elite, the film’s substance often falters. The plot meanders, and intriguing characters sometimes find themselves lost within the convoluted narrative. Scenes set in the Saltburn estate, seemingly shoehorned for a ‘Summer flick’ aesthetic, contribute to the film’s occasional lack of cohesion.

It is these peculiar story choices that start to make the audience lose connection with the characters also. Elordi provides a wonderful performance, but when acting out cheesy and almost obvious cliché scenes, the Oxford accent can grow tired and frustrating. The story, as a whole, has some superb writing and is generally very well crafted, but massively disappoints with a twist in the final minutes that could have been spotted from the starting line. Furthermore, Fennel seems to be slightly tone deaf to many of the issues of today’s environment that are almost commented upon in her film, but not quite.

…blurs the lines between summer romance and social thriller

Fennel, no stranger to the world of landed aristocracy, crafts a film that exists in a peculiar vacuum. At a time when so-called ‘Eat the Rich’ films like The Menu and Parasite are becoming increasingly popular and timely as they criticise the wealthy, Saltburn seems torn between condemning and sympathising with its affluent characters. It becomes challenging for the audience to navigate their feelings when faced with scenes that oscillate between the grotesque and the intimate, leaving an uncertain blend of detestation and adoration.

Verdict:

In this cinematic landscape, Saltburn stands as a visually stunning yet thematically conflicted piece. It treads the delicate line between style and substance, occasionally losing its way in a narrative that struggles to reconcile the repulsive with the sympathetic. As the credits roll, one is left with a sense of awe and bewilderment, appreciating the beauty while grappling with the lingering uncertainty that accompanies a film of such polarizing dichotomies.

Rating: 6/10

Enjoyed reading this review? Check out some of our full-length reviews on the best films of the year:

Review: Oppenheimer | Redbrick Film

Review: The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes | Redbrick Film

Comments