Social Secretary Ella Kipling, Life&Style Editor Julia Lee, Culture Editor Leah Renz, and Culture Writer Charis Gambon come together to give us their take on their top ‘spooky’ piece of art

Content Warning: This article contains themes of war, death and alcohol dependency.

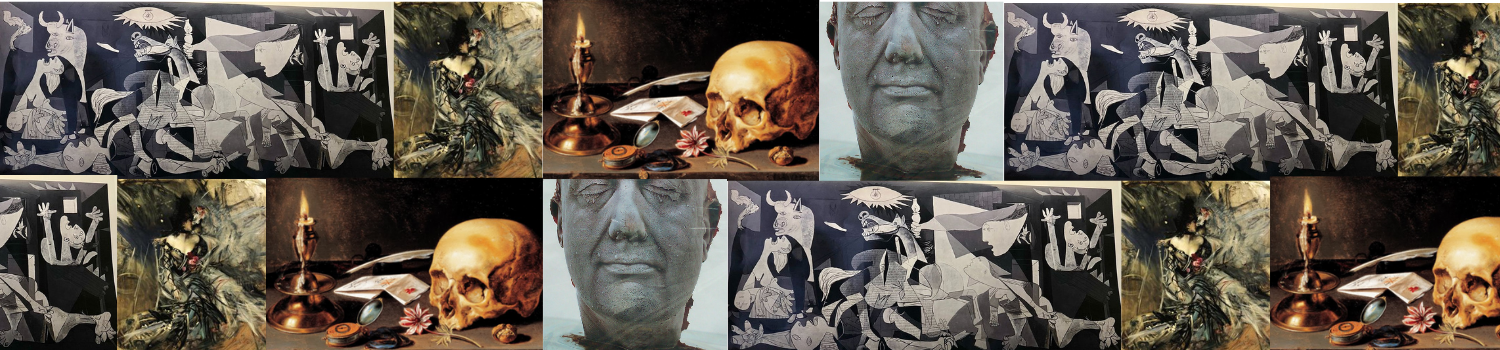

Guernica by Picasso

At first glance, Guernica may just seem like a painting filled with blue and black shapes, but when looking closely, the artwork is one of pain and suffering portraying the devastating effects of the Spanish Civil War.

Standing at 11.5 feet (3.5 meters) tall and over 25 feet (over 7 meters) wide, the painting is displayed in the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid. Seeing the painting in person is a brilliant experience as the sheer size of the canvas allows you to fully take in the details of each of the figures portrayed and the anguish on their faces. The piece was a response to the 1937 bombing of Guernica, a Basque Country Town in northern Spain.

Harrowing details in the piece include faces screaming in pain, limbs scattered around, and hands reaching out in desperation. For me, the ‘spooky’ aspect of this painting is the story behind it, that the people portrayed were not mere figments of Picasso’s imagination, but real victims of a vicious war which took the lives of roughly half a million people. The chaos and pain portrayed in Guernica echoes the real experiences of real people, which is perhaps the scariest thing of all

The Museo Reina Sofía states that the artwork constitutes ‘a generic plea against the barbarity and terror of war,’ and can be interpreted as ‘a testimony to the horror that the Spanish Civil War was causing and a forewarning of what was to come in the Second World War.’ The chaos and pain portrayed in Guernica echoes the real experiences of real people, which is perhaps the scariest thing of all.

Ella Kipling

Self by Marc Quinn

I remember encountering Self for the first time, and approaching with mild bafflement – what was this human-head sculpture even made of? My confusion quickly morphed into disbelief and disgust as comprehension slowly dawned on me. Marc Quinn’s self-portrait busk was not made from some type of ruddy rock, or dyed wood as I had first suspected; it was in fact moulded from 10 pints of the artist’s own blood. Quinn took the concept of a ‘self’-portrait to the next level

Safe to say, Quinn took the concept of a ‘self’-portrait to the next level. To keep its shape, the sculpture is immersed in frozen silicon, and must always be connected to an electrical power source to remain sufficiently cold enough. This dependency is reflective of the Quinn’s own dependency on alcohol at the time of creating this piece. Every five years, the piece is re-moulded to reflect the ageing of the artist, so that it winds up representing the ‘Self’ of the artist in many more ways than one.

A busk of yourself, made of your own blood, which ages with you in an anti-Dorian Gray process, seems like a strong enough contender to be labelled “spooky”.

Leah Renz

Vanitas Still Life by Pieter Claesz

Vanitas is a stylistic movement that boomed in 17th century Holland, and Pieter Claesz is one painter of these still lives. Throughout his career, he created many works representative of the macabre genre – at first glance, you see a skull, almost out of place on a table of fruits, utensils, and trinkets. Upon closer inspection, one realises that they have one thing in common; they are all things in decay.

Often associated with the movement is the proverb ‘Memento Mori’: ‘remember you must die.’ The name ‘vanitas’ is derived from the Bible, lending a Protestant sensibility to the painting’s subjects, who are themselves earthly possessions chosen carefully to convey some heavenly lesson. An empty wine glass for overindulgence, ink and paper in disarray for pride, instruments for vanity. Transient pleasures are nothing compared to the transcendence of virtues. The items are grounded in their realism, and grounded within the piece to the surface of a table. The paintings may have a light source, either a candle or a focused beam from above, but the scene is muted and always cloaked in dimness. Often associated with the movement is the proverb ‘Memento Mori’: ‘remember you must die.’

Vanitas has influenced all sorts of mediums, so you have almost definitely seen it in action – whether it is the still-lives themselves in an art museum, book covers for thrillers, tattoos on someone’s arm, or even (this is unverified) anime.

Julie Lee

Spanish Dancer at the Moulin Rouge by Giovanni Boldini

The Spanish Dancer is painted in a dark colour palette with shades of black and grey used in the painting. The pink and red roses in the centre of the painting stand out in terms of colour but are not the first place your eyes look at; the female figure stands out against the chaotic background behind her. The painting has an extremely gothic feeling about it.

The painting has an extremely gothic feeling about it

Charis Gambon

Enjoyed This? Read more Art Content here!

Exhibition Review: Anicka Yi at the Tate Modern

Comments