Comment writer Luisa Connors argues for free libraries in all primary schools to encourage wider reading for children.

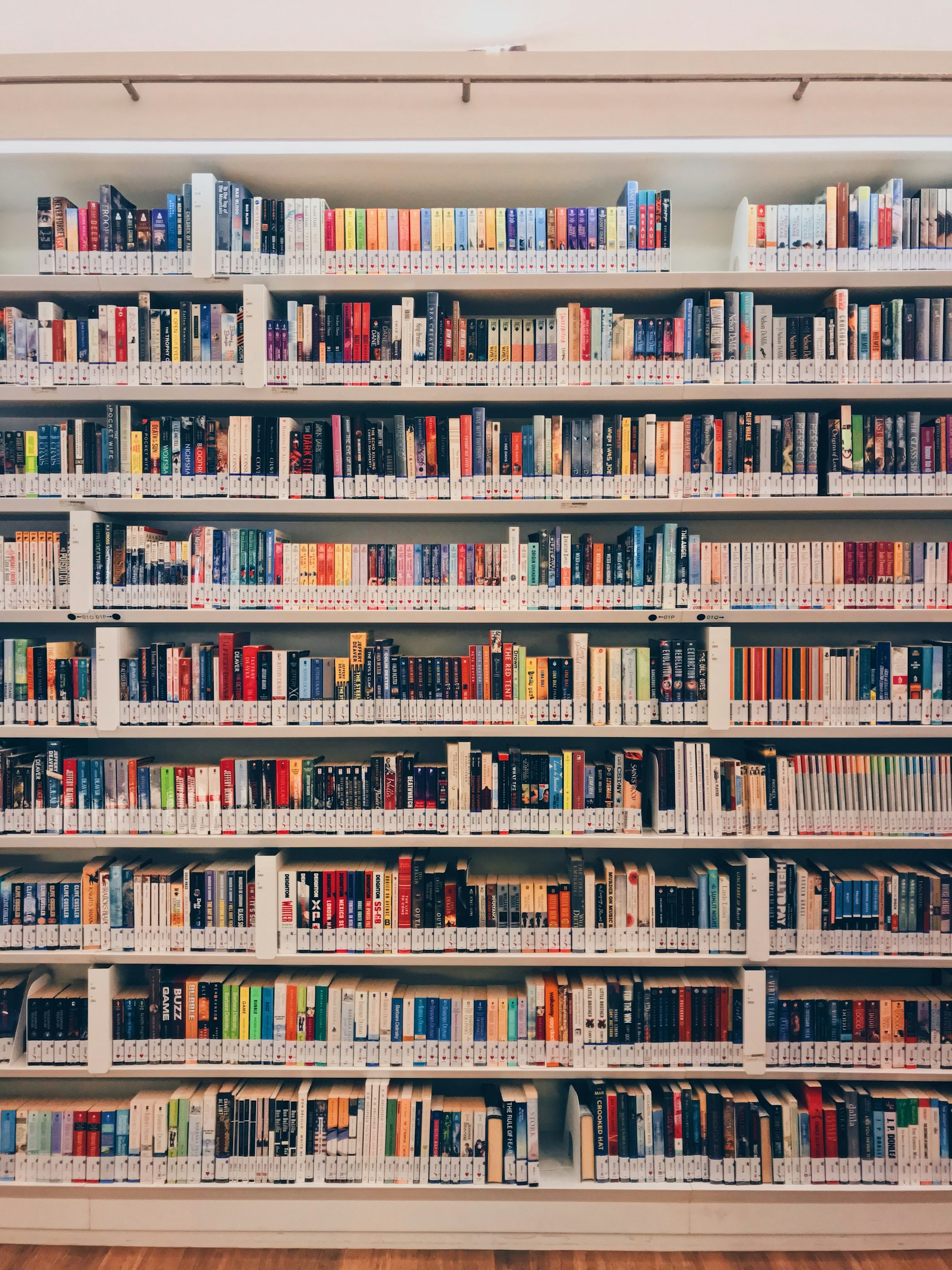

In 2023, the Department of Education published their scheme of ‘Reading for pleasure’, an ongoing initiative which aims to encourage active and enthusiastic reading habits for children in primary schools. Yet, as of 2022, one in nine schools in England don’t have a library. This number is even higher in Wales (25%), Scotland (25%) and soars in North Ireland (41%). Reading is a crucial skill, and as a student teacher currently working in primary schools, it is one I wholeheartedly believe needs to be encouraged in schools. With the number of children choosing to read in their spare time swiftly dropping to a 15 year low, is it not more crucial than ever to ensure schools have resources to nurture life-long readers?

The phrase ‘learning to read, and reading to learn’ has appeared frequently during my studies. It refers to the process of reading acquisition, first beginning with decoding (otherwise known as ‘sounding out’) words, and then moving onto comprehending full texts.

Certainly, children are being taught how to read for a test, Key Stage 2 SAT results displayed a rise in literacy attainment, jumping from 73 to 74% between 2019 and 2022. However, reading is not only for the purpose of testing, I believe that children should be encouraged to read for purposes beyond the curriculum. In order to do so, students need to be able to access a wide range of books.

According to recent research by the National Literacy Trust, fewer than half (47.8%) of children aged between 8 and 18 claim to enjoy reading. Even within this percentage, only 28% of children stated that they read daily. In response, the government has pushed the value of ‘Reading for Pleasure’, stressing its importance for educational and personal development. Children who read regularly reported increased intrinsic motivation for learning and improved well-being.

Only 28% of children stated that they enjoy reading

Some may argue that public libraries could be sufficient. Libraries have kids sections after all, so why can’t children go there? Yet, it is important to remember that books need to be as accessible as possible in order to attract a wide audience. For example, a child who is already disinterested in reading is unlikely to travel to their local library (which may not even be that local) to pick up a book. Moreover, traveling to a library takes time and often needs a willing parent or guardian, which can be difficult for working parents. Having a library situated in the very place that children spend most of their time daily is the best way to make reading accessible and appealing. As importantly, school libraries are led by experts in children’s literature, who are able to source and recommend a range of books and act as a role model to young readers, alongside other teaching staff.

So then, what can the government and educational institutions do to promote pathways to reading? For starters, adequate funding is paramount. In 2023, the primary school library budget had decreased by 16% compared to the year prior. During a cost of living crisis, where 1 in 5 parents reported buying fewer books for their children therefore, it is now more than ever that children, especially those living in deprived areas, need to have access to reading.

It is now more than ever that children…. need to have access to reading

Adequate funding should ensure that the school library is stocked with a diverse range of genres, authors and themes that students from a range of ages, cultural and ethnic backgrounds can relate to. It should enable schools to stock high-quality books which encourage engaging reading. This includes stocking books which reflect the interests, attainment and cultural diversity of students and promote representation in a positive manner. Moreover, these texts need to be embedded into the curriculum, as many students are advancing to GCSEs having never studied a book by a black author. There is a reduced number of children’s titles which feature characters from non-white backgrounds. It should be noted that this issue stems back to the number of children’s titles which feature characters from non-white backgrounds. Although figures have increased from 30% in 2022, from 4% in 2017, it is now necessary to push for further high-quality, diverse representation in children’s literature to allow children to relate to their stories.

Ultimately, children and young people need to be given opportunities to read a range of high-quality literature. In order to ensure the newer generations reap the benefits of reading, they first need to have access within their schools. Without adequate funding, particularly for low-income backgrounds, children miss out on the educational, psychological and social benefits that reading has to offer. It is therefore vital that all UK schools have a library.

For more Comment articles on education:

The Cost of Becoming a Student

Crumbling Schools: A Structural Weakness

Sunak’s plans to cap ‘rip-off’ degrees will leave many students without enough options

Comments