With the announcement that the UK will be continuing to operate a lockdown policy for ‘at least’ the next three weeks, speculation as to when the UK might reach its peak in the number of coronavirus cases continues

Data provided by the government seems to suggest a flattening of the curve across the last week – but do these statistics really provide us with the whole picture?

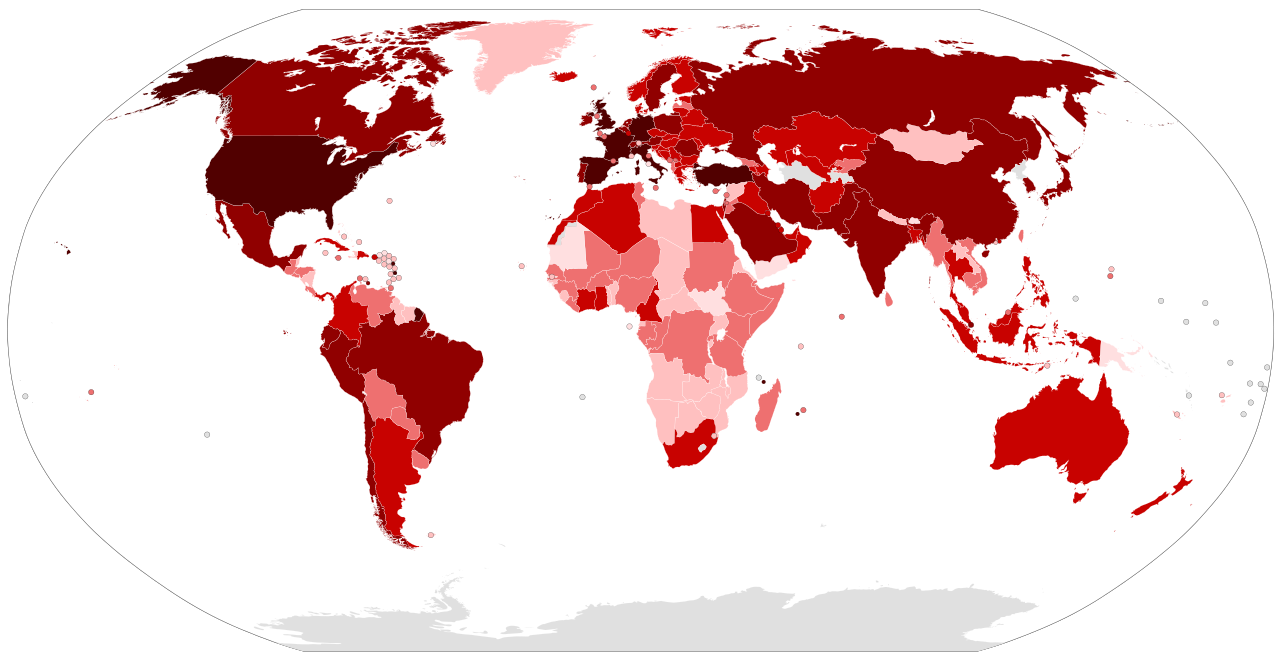

As of 21st April, the global figures released by the World Health Organization (WHO) stand at 162,956 deaths and 2,397,216 confirmed cases, with the epicentres of the pandemic having now shifted to Europe and North America.

In the UK, statistics are being released daily regarding the number of confirmed cases, which, as of 5pm on the 20th April, had reached 129,044. The reported number of deaths stands at 17,337. What remains more complex however, is understanding how many of these deaths are caused directly by the coronavirus, as opposed to the number of patients who died due to pre-existing conditions while also having COVID-19 in their systems. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has begun to investigate this issue, and has so far reached the following conclusions: The virus was the primary cause of death in the majority of cases; and those killed by the virus often had a pre-existing health condition that meant their risk of death was increased as well.

The figures released by the government also fail to provide a comprehensive overview of coronavirus-related deaths outside of hospitals. Those who reside in care homes, or who remained at home whilst ill, are not accounted for in the statistics published by the government, despite the fact that they often represent a demographic considered to be more at risk.

After a series of outbreaks were reported in care homes across the country, opposition parties and media outlets began to call for the reporting of statistics relating to care home deaths, as well as increased supplies of PPE to those working in the social care sector. The figures supplied by the ONS account for these deaths in the wider community, and are different to those provided by the government due to the fact that they are formed based on registered death certificates. In the period up to 10th April, the ONS reported 1,043 deaths in care homes as a result of the pandemic. As the ONS statistics are published with an approximate ten day delay, it must be assumed that the figures released by the government on a daily basis are an underestimate of the total number of deaths.

In the daily Downing Street briefing on 15th April, Secretary of State for Health and Social Care Matt Hancock praised the work of Sky News journalist Nick Martin, whose ‘excellent’ reporting had brought to light many of the issues facing those in the social care profession. The government has since released their new ‘adult social care action plan,’ which promises more PPE to those working in social care, as well as reinforcing the fact that ‘visits at the end of life are important both for the individual and their loved ones and should continue.’

Certain geographical areas of the UK are also reporting much greater numbers of deaths due to coronavirus than others. Perhaps unsurprisingly, London has emerged as the epicentre for the virus in the UK. Fairly early on in the fight against COVID-19, the West Midlands was also recognised as a hotspot after recording the highest number of deaths outside of London. In an ONS release regarding deaths up to 10th April, it was found that 37.0 percent of deaths in the West Midlands in week 15 were related to COVID-19.

Birmingham MP Khalid Mahmood suggested at the time that this could be linked to the fact that some elderly members of the Muslim and Sikh community were struggling to follow the social distancing guidelines: ‘Part of it is because they feel religious observance is more important now than ever – they feel they may die and lose loved ones – so they need to pray. These are people who have incredibly strong religious convictions and it’s hard for them to stay away.’

As the virus has spread, new hotspots have emerged across the country. Urban centres tend to be the hardest hit, due to the concentration of people and businesses in those areas. According to updates issued by the government on 20th April, London is still displaying the highest number of confirmed cases, with a total 21,654. The regions of the North West and the South East are now second and third in terms of the total number of cases recorded, having overtaken the West Midlands. Despite this, Birmingham still remains one of the upper tier local authorities with the highest number of cases, recording 2,310.

What the overarching figures also struggle to convey is that a disproportionate number of deaths as a result of COVID-19 are from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities. Of the 13,918 patients who had tested positive for COVID-19 at the time of death, up to 5pm on 17th April, 16.2 per cent were of BAME ethnicity. This percentage seems like a marked increase compared to the 7.5 percent Asian population and 3.3 percent black population reported in the 2011 UK census. Speaking to PA news agency, Mohammed Abbas Khaki, a GP with Barking, Havering and Redbridge University Hospitals NHS Trust, said: ‘Existing inequalities will be more greatly exposed at a time of crisis. For example, south Asians live in more deprived areas and have more diabetes, kidney and cardiovascular disease.’

‘Many of these workers may also be in key worker jobs – combining their frontline roles with their living arrangements might be a reason that we are seeing so many of the BAME population in intensive care units.’

While part of a global trend, figures in the UK also suggest that men are more likely to die from COVID-19 than women, despite the fact that women are equally as likely to contract the illness. Data from the ONS revealed that in all age categories, death rates were higher for men. These findings are also similar to those observed by epidemiologists during the previous SARS and MERS outbreaks, in which men were also seen to die at a higher rate than women. One study, which looked at over 44,000 confirmed cases in China, found that the male fatality rate was 2.8% compared to 1.7% for women. While the reasons behind this have not been conclusively investigated, speculation has suggested that it could be linked to lifestyle factors, such as the fact that men are more likely to be smokers, in which case their lungs could potentially be compromised prior to contracting the disease. Other suggestions include the fact that women have been shown to demonstrate a stronger immune response, noted in the way they fight off viruses and respond to vaccinations. Again, scientists are not entirely sure as to why this is the case, but biological factors such as the production of estrogen and the presence of two X chromosomes may play an important part.

One other area of concern with regards to the death toll are the UK’s prisons, where there have been 13 reported deaths and 218 confirmed cases. Worries here have arisen based on the fact that an outbreak in such a confined space would be very difficult to contain. Frances Crook, Chief Executive for the Howard League for Penal Reform, believes that if the virus did make it into a prison setting, ‘it would spread and multiply like wildfire.’ Speaking in a video conference addressing Parliament’s Human Rights Committee last Monday, the Justice Secretary maintained that ‘We are able, so far, I am glad to say, to maintain not only the degree of healthcare that you would expect us to apply to individuals who are stricken by this appalling illness, but also the dignity that anybody deserves when they are reaching the end of their life.’

Comments