Culture Writer Frankie Rhodes reviews The Magician’s Elephant, writing that despite some individuals shining through, the audience was still left wanting more

Following 2019’s The Boy in the Dress, the heartfelt, gender-binary crushing smash-hit, we all waited with baited breath to see what the Royal Shakespeare Company would do next. Their next musical, The Magician’s Elephant, is also based on a children’s book, this time transporting us to the war-torn, steampunk town of Baltese. It tells the tale of a young orphan, Peter, who receives a prophecy from a fortune-teller that the unexpected arrival of an elephant, conjured by a local magician, will reveal the secrets of his lost family. Yet despite a promising set-up, this production felt like a patchwork of other recent musicals, failing to find its own distinctive voice.

“This production felt like a patchwork of other recent musicals, failing to find its own distinctive voice

When the curtain rises, we are greeted not with a world-building chorus number, but with the solo narration of Amy Booth-Steel. Despite her best efforts to introduce us to the mysterious town of Baltese, accompanied by a map-like projection, this opening lacked energy. Perhaps, this was designed to portray the dreary nature of people recovering from war. When we do meet the villagers, they have the frazzled nature of a Sweeney Todd cast, clad in grey and monotonously lamenting memories of loved ones. At the centre of this is Peter (Jack Wolfe) who is being raised by Vilna Lutz (Mark Meadows), a no-nonsense military man after the death of his parents during the war.

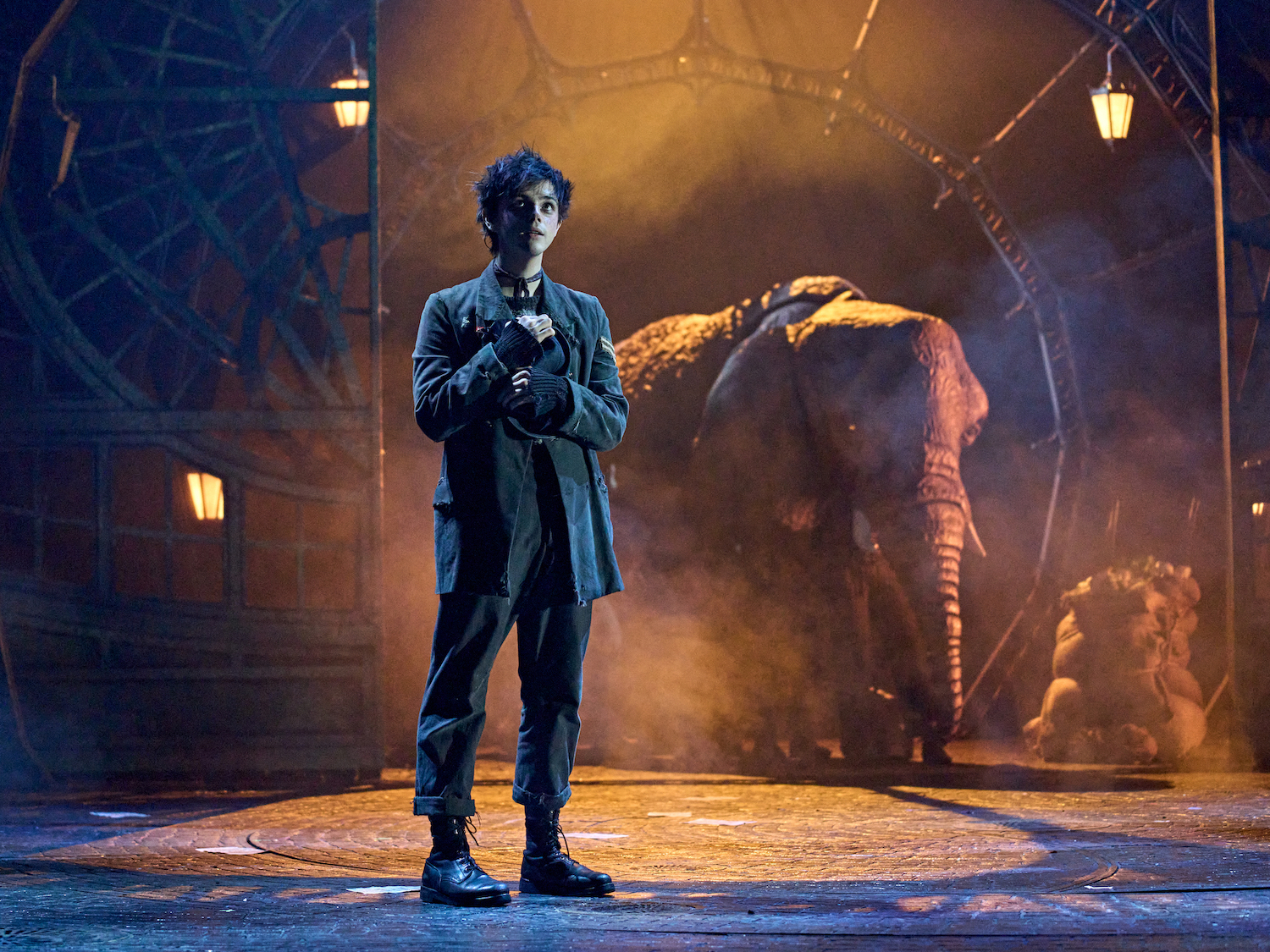

The set is minimal yet effective: with detachable staircases, and spirals of grey scaffolding lit with glowing lanterns, we are transported into Yoko Tanaka’s ghostly illustrated world. A revolving wheel allows Peter to march through the village, meeting grief-stricken merchants and starving families. From the very beginning, Jack Wolfe’s Peter is bright-eyed and high-spirited, exercising impressive vocals as he ponders his uncertain future.

Unfortunately, other characters are not afforded such a rich introduction, nor are their vocals quite as melodious. The Sondheim-esque feel of the music means that figures never quite reach their vocal range, and while this may be a deliberate choice, it risks minimising the talent of the cast. The magician, for example, is such a minimal character as to question his position in the title of the show, and the song he performs from jail frustratingly scrapes below his repertoire.

“There are a lot of characters to get to grips with, and because the first half an hour of the show favours exposition, many of the cast are introduced far too late

There are a lot of characters to get to grips with, and because the first half an hour of the show favours exposition, many of the cast are introduced far too late. Adele, for example, is expertly portrayed by Miriam Nyarko as an intelligent, adventurous star to parallel Roald Dahl’s Matilda, yet we do not meet her until way into the second act. Ensemble scenes in the first half, such as the glittering opera scene and the farcical police number, come at the expense of real character development.

Undoubtedly, there are individuals that shine through, despite their limited time in the limelight. Forbes Masson, for example, the frantic, rosy-faced police chief, is an important source of comic relief, following on from his stunning role as the headmaster in The Boy in the Dress. The two villains of the ensemble, Count and Countess Quintet, are fabulous as they peruse the stage on an elevated platform, with Summer Strallen reaching remarkable operatic heights. And then, of course, there is the real star of the show – the elephant.

The themes surrounding this beautiful beast fall somewhere between American Horror Story’s Freak Show and Hollywood’s The Greatest Showman. Yet, the production manages to break new ground by establishing the elephant as a character from the very beginning, addressing her as ‘she’ and using spectacular 3D effects for the puppet, ranging from stomping feet and a trumpeting snout to mournful, blinking eyes. The elephant really is spectacular, but we spend more time hearing about her from the characters (who bizarrely develop a kind of elephant religion-slash-cult), than actually seeing her in the flesh.

Some of the most intimate moments are those when Peter interacts with the elephant. Akin to novelistic sequences such as Michael Morpurgo’s The Butterfly Lion, the human and animal establish a touching rapport. Peter’s number delivered to the elephant, where he muses on their similar sense of loneliness and captivity, was one of my favourite parts, matched only by the passionate song of the Matienne family. This couple, Leo (Marc Antolin) and Gloria (Melissa James), are another two characters who aren’t given enough stage time, and Gloria’s beautiful voice is tragically only heard for one five-minute stretch.

“You find yourself constantly wanting more from the chorus numbers as well as from the solos

Director Sarah Tipple manages to create a consistent and evocative dystopian atmosphere, and there are some important casting choices, with disabled actor Renu Arora taking on the role of an aristocrat who is injured by the elephant crash-landing into the opera house. In many ways this is a musical for our post-lockdown society, yet the sense of hopelessness is slightly too rigid.

While each and every cast member is more than capable of carrying the show, you find yourself constantly wanting more from the chorus numbers as well as from the solos. It ends on a heartfelt message, solidifying the appeal of Kate DiCamillo’s book, yet the production still struggles to come to life as an animated creation. With a bit more streamlining this could be a fantastic show, but for now it seems to rely too heavily on tropes and motifs from the ghost of musicals past.

Enjoyed this? Read more musical reviews on Redbrick Culture!

Comments