Culture editor Emily Gulbis praises the webinar on Joseph Chamberlain run by the University of Birmingham for beginning discussions about the University’s founder and his lesser-known actions as Colonial Secretary

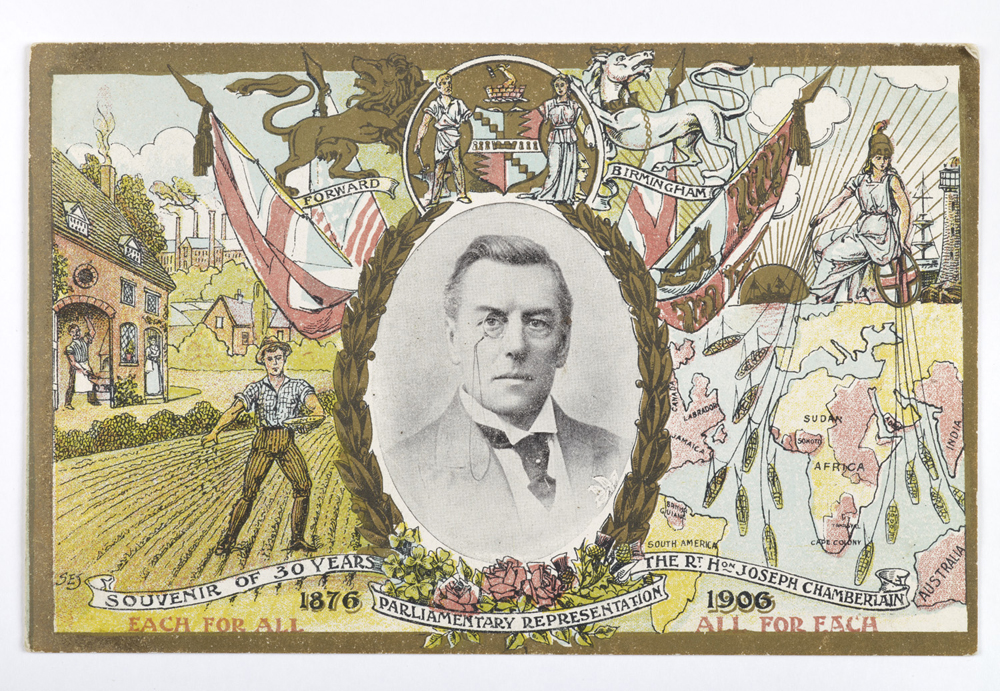

Who really is Joseph Chamberlain? Though best-known by students as the first Chancellor of the University of Birmingham, Chamberlain is more widely remembered as a politician, Mayor of Birmingham, and leading liberal reformer of the British education system. In recent months, with movements like Black Lives Matter, Chamberlain’s actions outside of the UK have been brought to light, to recognise his role in shaping the Empire.

For Black History Month, the University ran the webinar ‘Decolonising our History: Joseph Chamberlain, Birmingham and the British Empire.’ This is an important and positive step taken by the University to scrutinise the negative history as well as the successes of its founder.

The discussion’s aim was to have a reckoning with our shared history and to consider how we want to set the tone for looking at our University’s origins

The talk began with Professor Matthew Cole giving an overview of Chamberlain and his historical biography, reminding us of his multi-dimensional character. Born in 1836, Chamberlain was known first as a social reformer. In 1867, he and the then Birmingham Mayor, Jesse Collings, founded the Birmingham Education League, which wanted government grants for schools that would be managed by local authorities, and for more inspections to raise education standards. This was a striking reform, given that at this time, only half of children went to school and only a quarter of schools were inspected. Chamberlain spoke on these changes saying ‘It is as much the duty of the State to see that the children are educated as to see that they are fed.’ He was a pioneer for improving education, which is why the University sees him as an important figure to remember.

Other liberal changes he made were to give control of gas, water and street lighting to councils, founding the free Birmingham Art Gallery and Museum, and clearing the slums of Birmingham.

However, there is little recognition of his role as an imperial politician at the University. He was a divisive figure and the University should acknowledge this. The talk stressed the need for there to be a general understanding among students that he had a hand in shaping Empire.

Chamberlain several times sanctioned the use of violence against insurrection in South Africa in order to expand British rule

Chamberlain left the Liberal Party, disagreeing with their stance on Ireland, saying it should not be allowed Home Rule. As Colonial Secretary, Chamberlain was instrumental in the Second Boer War, 1899-1902, a combat between the British and the Dutch over who controlled South Africa. In this War, the British introduced concentration camps under Lord Kitchener that resulted in the genocide of thousands of Boers. He was also part of a Conservative policy towards South Africa which lead to the exportation of gold, leaving this area unstable and disenfranchising black people.

Despite this, by comparison to other imperialists like Cecil Rhodes and Clive of India, Chamberlain was less extreme in his views on Empire. Known as the Imperial Reformist, he did want to improve the conditions in the countries such as campaigning for imperial tariffs which would make trade cheaper for countries within the British Empire.

Rebecca Bridgman, Curatorial and Exhibitions Manager at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery then spoke about The Past is Now, a previous exhibition which featured information boards on Joseph Chamberlain’s actions as Colonial Secretary. This is another example of how Birmingham is starting to address his actions as an imperialist.

Masters student, Ikram Ayaanle Hassan raised the important question, which she and others at Chamberlain Highbury Trust are trying to answer: what were the global impacts of Chamberlain’s imperial policies, and how much have they shaped modern Birmingham? We must not forget that much of modern Birmingham is built on imperial exploits across many nations that were initiated by men like Chamberlain.

However, he enacted beneficial policies as an MP, like founding the University of Birmingham, recruiting students of all classes and genders. From its establishment, the University of Birmingham has recorded having high numbers of international students, from around 150 countries, and an inclusive curriculum.

Chamberlain did have a hand in Empire, he participated in it and now we should acknowledge this. It is wrong to see these men in history as entirely good when in fact they had many failings. Otherwise, we run the risk of having a false perception of our history and this encourages denial of culpability.

Another step the University could take to improve Chamberlain’s legacy would be to invest in departments or modules that will teach students about imperial history and Empire

Whilst most students are aware of Joseph Chamberlain and have great affection for the buildings named after him, most are oblivious to this more controversial aspect of his character. Acknowledging this does not detract from his contributions to the University and local area but instead works to counteract the erasure of Britain’s colonial past.

Read more for Black History Month:

Decolonising Art Institutions: Display It Like You Stole It

Cultural Appreciation vs. Cultural Appropriation: The Adele Debate

Comments