Life and Style Editor Molly Day looks at the portrayal of football hooliganism in the British press, considering the classist values at stake

Historically, violence has been entwined with the traditions of football, earning its own title: ‘Football Hooliganism.’ Hooliganism is defined by drug use (particularly cocaine), destruction of public property and fan to fan violence. It occupies a particular spot within the social history of Britain, especially during the 1980s, and is often referred to as ‘the British disease.’

However, football hooliganism is not an entity of the past and the rates of fan violence have skyrocketed this year alone, highlighted by the statistics collected by the UK Football Policing Unit. The Times recently documented the disorderly behaviour of fans at a Leicester City v. Nottingham match, where Inspector Craig Berry described the fans (some as young as 12 years old) as ‘risk supporters.’ Authorities cited within the article appear to fear that the increased rates of drug use and violence reported in and around stadiums could imply a return to the rampant football violence seen in previous decades – a worrying precedent.

The increased rates of drug use and violence reported in and around stadiums could imply a return to the rampant football violence

Undoubtedly, there is a genuine deep-rooted history of violence in football and the victims of this violence should not be ignored. There are inherent identity politics within the sport, with fans mostly supporting teams based on a shared nationality or hometown. This, combined with the patriotism of competitions such as the World Cup has led to a longstanding culture of racism amongst fans. At its worst, football hooliganism has been seen to perpetuate this aspect of the game and make football games less safe for fans of colour, in particular black fans. Indisputably, this is an issue that should not be tolerated or excused.

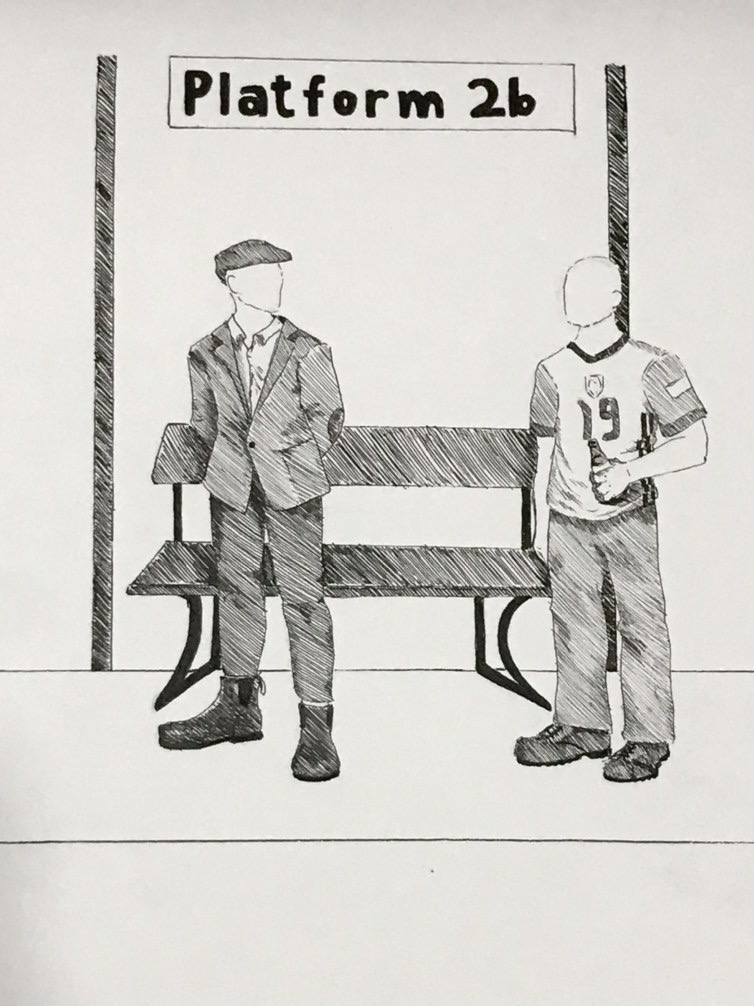

However, I wonder why there is such a social focus on the ‘football hooligan.’ With so much collected coverage of the ‘hooligan,’ I believe it is useful to think about what the term means to us. Why do we fear him? Why is the ‘hooligan’ more urgently monitored than any other anti-social sports fan?

Why do we fear him? Why is the ‘hooligan’ more urgently monitored than any other anti-social sports fan?

After all, there are cases of repeated violence in other sports. Horse Racing, a large-scale event with a similar culture and history of drinking and violence, for example, manages to evade the social analysis and labelling of football and its ‘hooligans.’ In fact, there is a history of mass violence at horse racing events, with violence occurring almost yearly. To give just two examples, nine men were sentenced after a ‘mass brawl’ at Goodwood racecourse in May 2018 and similarly, there was a mass brawl at Haydock Park racecourse in 2019. Not to mention the yearly violence at the Royal Ascot. In addition, there have been numerous reports of drug-use at the races too, particularly cocaine usage by both Jockeys and spectators.

When considering this information, I believe the reason there is not a replica term to describe unruly men who attend the races is because of its history as an upper-middle-class sport and royal tradition. When upper-middle-class people drink too much and become rowdy it is presented as loveable and comic: a Vice article from 2019 invites us to laugh at ‘Photos of Posh People Getting Absolutely Smashed at the Races.’ In contrast, I would argue working and middle-class consumption of sport and alcohol is depicted as threatening and distasteful. In fact, even the violence reported at Horse Racing events seems unfairly pinned on the attendance of the working class. A Daily Mail article reporting violence at the Royal Ascot blames the attendance of lower-class people on the increase in violence, describing “unsightly tattoos” and “women in cheap, tawdry dresses”. Here, I believe the British press are making an association between violence in sport and working-class status.

The British press are making an association between violence in sport and working-class status

Alongside fears that the sport is becoming more violent, I believe there is a clear association made by authorities between rowdy fans, gang violence and organised crime.

Interestingly, within its description of drug-use and physical violence The Times’ documentation of the Leicester City and Nottingham match also notes the designer clothing worn by the fans. In my opinion, this mention of designer clothing gives the article a strange tone. I believe such descriptions profile the hooligans as working class. There is a long association with working class people and designer clothing. An article from the Independent from 2004 highlights this long-term alignment between the working class and brands – they say that ‘chavs,’ who are defined by a ‘lack of education, taste for fighting and loud fashion tastes’ are the ‘not entirely welcome, saviours of the luxury goods market.’

Personally, I can’t help but compare this outdated, classist description with The Times’ description of ‘hooligans’ who ‘dressed and behaved exactly like older men, wearing a uniform of designer clothing.’ I think from this description, we can assume the men’s appearance is part of the police’s perception of them as disorderly. When you look at what kind of style they are describing, it is the fashions of working-class men. Furthermore, I think the article goes to a bizarre effort to characterise the fans within the stereotype of rambunctious, designer-clad hooligans – citing £60 gazelle shoes as extravagant ‘designer’ clothing as opposed to averagely priced, commonly worn trainers.

When I consider the football hooligan’s physicality, it is even more likely that the focus on the hooligan is not a greater, more reported issue because it is a more tangible threat than other anti-social behaviour but because of its associations with the working class.

Because of its associations with the working class

In my opinion, the presentation of football hooliganism does not derive from a specific craving for violence from football fans but from a wider desire to categorise working-class and lower-middle-class people as ‘uncivilised.’ I believe it is no coincidence that we are seeing a ‘re-rise in football hooliganism’ under a prime minister who wrote that working-class men are ‘likely to be drunk, criminal, aimless, feckless and hopeless.’ Is it implausible to suggest that having a leader with such beliefs could rally a kind of pre-millennium working-class hatred? Significantly, the height of football hooliganism was during the 1980s, under Thatcher, who found it such a social issue that she opened a war cabinet to tackle it. I believe when you consider that Thatcher lowered taxes for the wealthiest in Britain from 83% to 40% and more than doubled child poverty, it is convincing that her drive to tackle football hooliganism was class-focused.

Although there may be public disorder at football matches, it’s important to take a closer look at why the ‘football hooligan’ is such a present threat in our cultural eye. Why do we use the demonisation of football fans as an acceptable outlet to demonise working-class men?

Why Don’t You Read More From Comment:

You May Have Missed The Cabinet Reshuffle, But Its Implications Are Large

Record Numbers Sign up to Nursing Courses

Comments