Gaming Editor Louis Wright breaks down the fascinating ways in which film, filmmakers and philosophy intersect

Films are a powerful vessel for providing an insight into the world we live in. Thematic explorations of political, societal, and interpersonal relationships are barely the surface of the potential that a filmmaker has in providing their perspective of the world to their audience. By taking the world around them and their lived experiences in life, each filmmaker can use their unique perspective to inform their works, and if done correctly, allow their films to ascend to new heights.

On the level of a singular film, The Iron Giant (1999) is a reflection of the struggles of director Brad Bird at that point in his life. Following the murder of his sister at the hands of her estranged husband, Bird considered the idea ‘what if a gun did not want to be a gun?’ This idea permeates all aspects of The Iron Giant, from the character development of the titular Giant to the Cold War backdrop of the film. As such, The Iron Giant is a representation of and an outlet for the grief of its director.

In contrast, director Jordan Peele’s catalogue all pulls upon his lived experience as a Black man in the United States to inform the films he makes. Get Out (2017), Us (2019), and Nope (2022) all interlace the necessary components of their thematic storytelling and narrative with what it is like living in a racist system as someone who is oppressed. While vastly different stories, the themes of each film are connected to one another. This is to say these films could not exist separate from the philosophy and perspective of Jordan Peele and each other.

When done correctly this style of filmmaking, interweaving personal philosophy and storytelling, can make a seemingly disconnected career of filmmaking a cohesive body of work. None is more definitive of this fact than the films of Hayao Miyazaki. Miyazaki’s original works all feature a consistent array of themes that are reflective of his philosophy.

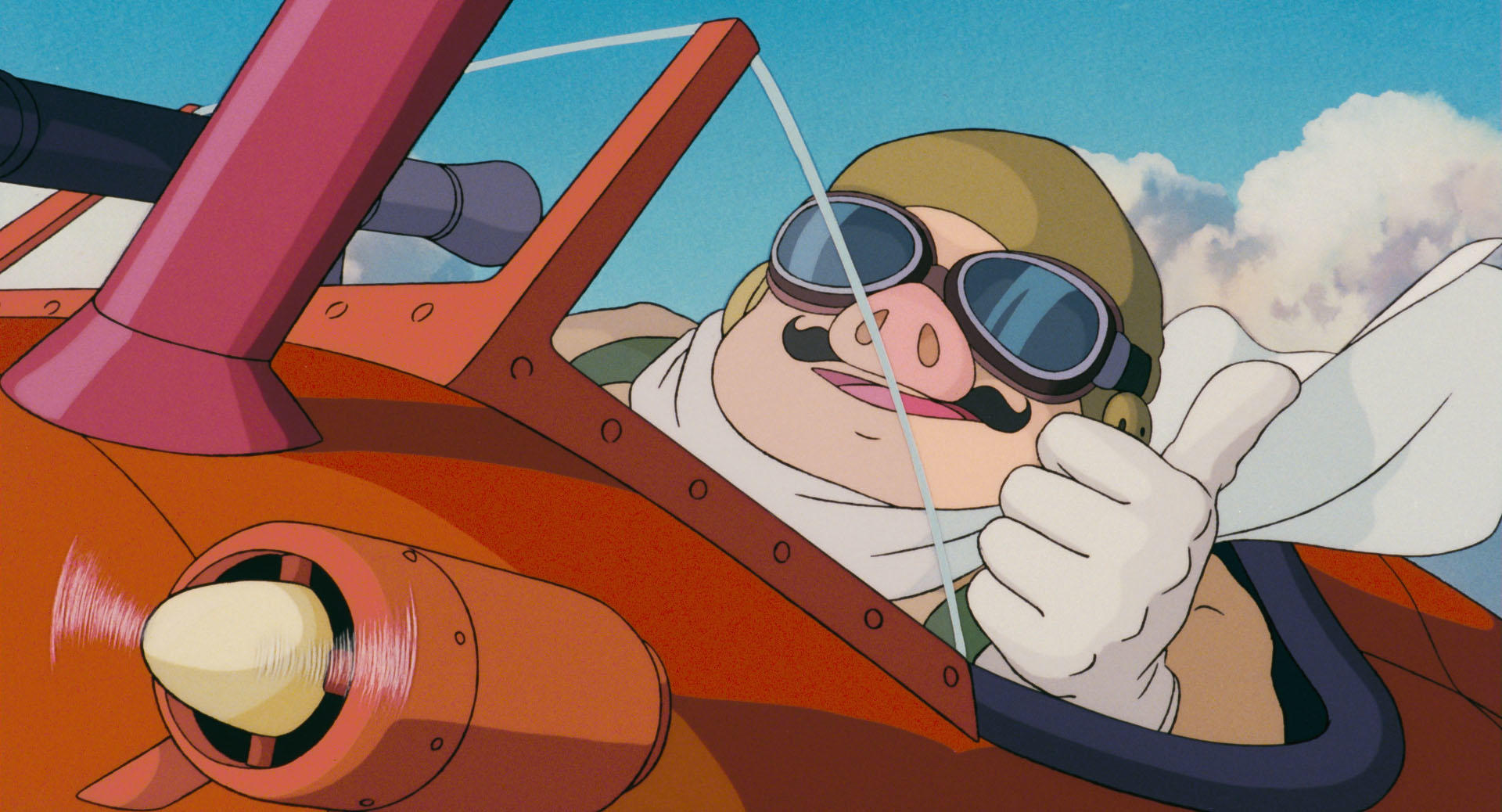

A renowned pacifist, many of Miyazaki’s films reflect this perspective in featuring strong anti-war messaging. Howl’s Moving Castle (2004) is a reflection on the pointlessness of war, as the one that the film is forefront to is established to have been caused by a misunderstanding between nations. This same view of the pointlessness of war is also seen in Porco Rosso (1992) and Princess Mononoke (1997) both being reflections of not only the needless destruction that war entails but the dangers of a fascist or dogmatic ideology.

On the other side of his explorations of the darker side of humanity, Miyazaki’s films also prominently reflect his environmentalist beliefs. My Neighbour Totoro (1988) features not only Miyazaki’s most iconic original characters, but ones that are guardians of the forest. The film, through these characters, is a reflection on the traditional beliefs of Japanese culture and how the union between man and nature can be used to heal. As a part of this Miyazaki examines the beauty of the natural world.

[My Neighbour Totoro] is a reflection on the traditional beliefs of Japanese culture and how the union between man and nature can be used to heal

While a surface level analysis of the thematic consistency of Miyazaki’s work presents it as similar to Peele’s in the sense that the different stories and environments present the same philosophy, The Wind Rises (2013) sets Miyazaki apart as not only a filmmaker but a philosopher. The penultimate film of his career, The Wind Rises is a semi-fictionalised exploration of the life of aeronautical engineer Jiro Horikoshi acting as a metaphor for Miyazaki’s wider career.

A commonly occurring aspect of Miyazaki’s filmmaking is the use of air vehicles in a wide variety of fashions. Whether they be for war, recreation, or transport only a select few films created by the director are missing the element that has almost become symbiotic with his work. Therefore, the film that brings planes and air vehicles to the forefront more than any other of its predecessors provides insight into the philosophy behind the use of these aircraft.

Within the film Giovanni Caproni, a spiritual mentor to Jiro from the past age of aeronautical engineers and self-insert of Miyazaki as a retiring artist, poses the question “Would you rather live in a world with pyramids, or a world without?” This quote, in reference to the creation and design of aeroplanes, is definitive to what planes mean within The Wind Rises and by extension the larger body of work for the director.

By asking whether the pyramids, one of the greatest wonders of the world and testaments to the power of human ingenuity, were worth the cost and pain that they took to build, from the labour and lives of countless slaves, Miyazaki asks the audience if the inherent link often found between beauty and tragedy is worth the price. In The Wind Rises no success comes for free. A constant cost is present that must either be paid or risen above to produce something truly beautiful.

By presenting the planes as a beautiful creation, like the pyramids a testament to human ingenuity and freedom, but also a terrible creation, for the destruction and death they can cause in wartime and to the environment, this metaphor transforms the perspective on all previous works that feature air vehicles.

Porco Rosso’s usage of aircraft is simultaneously beautiful in the fact that they are the last connection that Porco has to his life as Marco, but also terrible in that they are the sole source of conflict within the film. In Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989) aircrafts and flying are what allow for Kiki to make a connection with her first friend in Tombo, but are also responsible for her burn-out and subsequent depression. Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) features air vehicles being used for war and as a representation of the destruction that technology can bring, but also – when used effectively – helping to save not only people but the environment it endangers.

This link between beauty and tragedy, how something beautiful can cause tragedy, or how a tragedy can allow beauty to arise, can be used to define not only Miyazaki’s films but the themes within them. Many of the previously mentioned films that feature war or damage to the environment also feature ways in which love conquers or the potential for restoration. Whenever Miyazaki examines something tragic in his films he also explores the connected beauty and vice versa.

Miyazaki can be described as a philosopher over a filmmaker

Miyazaki can be described as a philosopher over a filmmaker. His perception of the world and his beliefs both politically and socially are so inherently necessary for his films to function that they are extensions of himself. Therefore, he is exemplary of the power that cinema and film can have to convey the director’s opinions and personal insights to the world.

Film is inarguably an art form. The medium can incite personal, intimate conversations with its audience in a way that no other can. A director’s philosophy bleeding through to the work they create elevates a film beyond just the surface level. When this is taken to the extent of an entire career, with consistent themes and philosophy being explored by a master of the craft it can create a filmography that is truly beautiful.

Liked reading this feature? Try these other features from Redbrick Film:

Redbrick Rewind: Theatre of Blood Turns Fifty | Redbrick Film

The Influence of the Nuclear Bomb on Japanese Cinema | Redbrick Film

Hollywood at War: the Writer’s Guild Strike Explained | Redbrick Film

Comments