Culture Editor Leah Renz reviews the Courtauld’s two-room exhibition on Vincent Van Gogh’s self-portraits

The Courtauld’s two-room exhibition is a short and sweet introduction to Van Gogh and his self-portraits and surprisingly satisfying despite its small size. The exhibition covers only a relatively small period near the end of Van Gogh’s life, but this period is especially experimental, and the moment where Van Gogh develops the style for which he is so well-known. Surprisingly satisfying despite its small size

Curating paintings from such a brief time span throws the differences between the works into a more incredible light because they showcase the intense rate of experimentation which Van Gogh was undergoing during this time. One excellent example of this was two paintings, hung side by side, which Van Gogh had created within a week of one another. I will not spoil the differences, but I can promise that they are dramatic, and lead me to reflect on the transience of emotions and states of mind, and how these can be expressed especially through the intimate genre of painting that is portraiture.

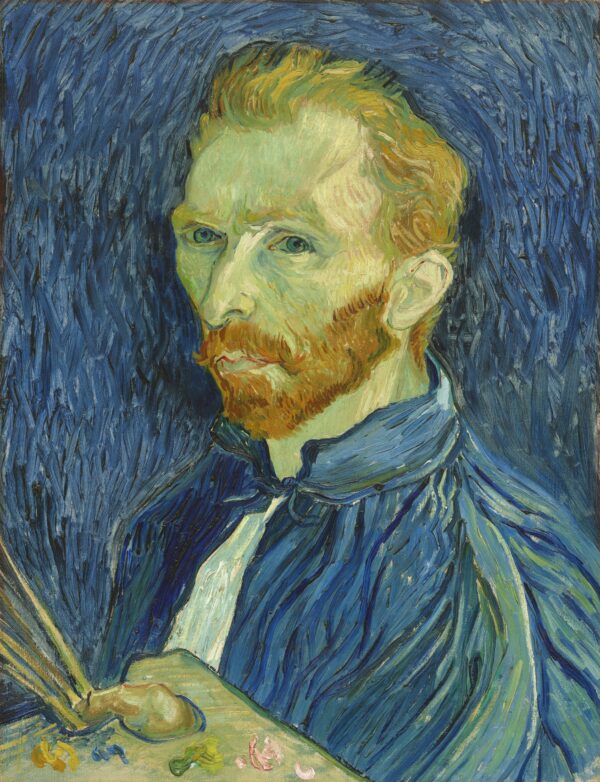

The intimacy of this exhibition, in size and content matter, is its biggest strength. The eyes of Van Gogh, looking out of his works from over 100 years ago, are sometimes far-off and contemplative, and other times piercing, even challenging. These changing expressions, and the accompanying changes in colour and style, ensured that the exhibition, despite having a homogenous subject matter, was never monotonous. The eyes of Van Gogh […] are sometimes far-off and contemplative, and other times piercing, even challenging

A detail I have loved in other Van Gogh exhibitions (most recently, The Potato Eaters: Mistake or Masterpiece? at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam) and which was also included in Van Gogh’s Self Portraits is the direct quoting of Van Gogh’s letters. One extract, from a letter to his younger brother Theo, explains the necessity of portraits even in an age of photography, saying that ‘painted portraits have a life of their own that comes from deep in the soul of the painter and where the machine can’t go’.

I love these personal details, not only because I often find Van Gogh to be an eloquent writer, but because it brings him to life in my imagination as a man with a brother, for example, and who struggled with his art and making a name for himself. These letter extractions, though highlighting the human behind the masterpieces, do not run against the exhibition’s aim to ‘dispel the notion that Van Gogh’s portraits were simply outpourings of raw emotion’. Instead, they emphasise the effort and work behind the art, produced not because of his mental illness, but in the face of it.

This exhibition will not only leave you in awe of a man who firmly believed in the power of art to heal and ‘fortif[y] the will’, but also you will be unwearied enough (from only two rooms) to contemplate with curiosity what you have just seen.

Enjoyed This? Read more from Redbrick Culture here!

Exhibition Review: A Gift to Birmingham at IKON

Comments