Gaming Editor Louis Wright looks back across the renowned career of acclaimed director Hayao Miyazaki

Few directors have the reach and acclaim of Hayao Miyazaki. Known for his works at Studio Ghibli over the last 40 years, he is easily one of the most well received and beloved filmmakers in history. With a seasoned history in animation, with some of the most recognisable characters and films in the cinematic landscape, Miyazaki is a director whose career has no film that is not filled with his passion and care for the craft.

His feature length directorial debut came in 1979 with Lupin the Third: The Castle of Cagliostro. While an outlier in Miyazaki’s filmography, both being the only one not released by Studio Ghibli and being of a significantly more comedic nature, the film presents a style still recognisable to the director. Through its fluid animation and general mystique, Lupin the Third is a solid launchpad into the career of Miyazaki.

Valley of the Wind is where the start of the typically recognisable aspects of Miyazaki’s filmmaking become present

Miyazaki’s second picture was released in 1984, that being Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. Valley of the Wind is where the start of the typically recognisable aspects of Miyazaki’s filmmaking become present, these being the exploration of anti-war and pro-environmentalism themes, the concept of love conquering all, and his excessive use of planes and aircrafts.

The film is iconic for its use of especially haunting imagery to convey the impacts of environmental disaster, towards the finale of the film. It was released to universal acclaim in Japan, not seeing a full release in western markets until over a decade later and is cited as an influence on the genre of anime, as well as being the direct cause of the founding of Studio Ghibli.

Helping found Studio Ghibli in 1985, Miyazaki directed and released the studio’s first film in 1986, that being Laputa: Castle in the Sky. Following on from Valley of the Wind, Castle in the Sky has a greater exploration of the concept of love conquering all, with that being arguably the frontal focus of the film. It also sees more of Miyazaki’s expert world building with the world that the film takes place in being well-established and explored over the runtime, with iconic and recognisable features stemming from its inspiration in Welsh mining towns helping it stand out among Ghibli’s other exploits. The influence that this film has had upon culture is not to be understated, with the “Laputa Effect” on Japanese cinema being cited and being said to be an influence on the modern steampunk genre.

My Neighbour Totoro released in Japan in 1988 and, with it, Miyazaki was truly propelled into the spotlight of the western markets for the first time. It is a film that is remembered remarkably well, being a phenomenal character driven story that keeps investment despite having relatively little plot to speak of. Its exploration of the benefits of nature are particularly in keeping with the trends set by previous Miyazaki films, and while the world it explores is particularly grounded to a traditional Japanese setting, the fantastical elements of Totoro fit seamlessly. Moreover, due in part to being a character driven story, My Neighbour Totoro has incredibly memorable and likeable characters who make the experience entirely relatable.

To talk about My Neighbour Totoro is also to talk about the cultural impact that it has. Totoro (the character) has had an immense impact on pop-culture iconography since the release of the film, appearing on endless amounts of merchandise and making cameo appearances entirely unrelated to his original film (for example Toy Story 3). He is easily one of the most recognisable animated characters made, helping lend to the staying power of My Neighbour Totoro and the general iconography of Studio Ghibli and Miyazaki as a whole. Overall, My Neighbour Totoro is arguably Miyazaki’s most important film in terms of his staying power in the echelons of cinema being a film that is both beloved inside and out of the cinematic landscape.

Grounded charm and stellar animation

Miyazaki continued with his more character driven and story-light films with his next release Kiki’s Delivery Service in 1989. Acclaimed for its grounded charm and stellar animation, it is fondly remembered for its exploration of Kiki’s character- a young witch wanting to find independence and her place in the world. The film resonated with viewers for its exploration of subjects not often touched on in the era, such as depression and self-doubt. It also continued to provide the typical aspects of Miyazaki’s outings such as love (both platonic and romantic) being a present aspect throughout and aircrafts of many varieties making appearances.

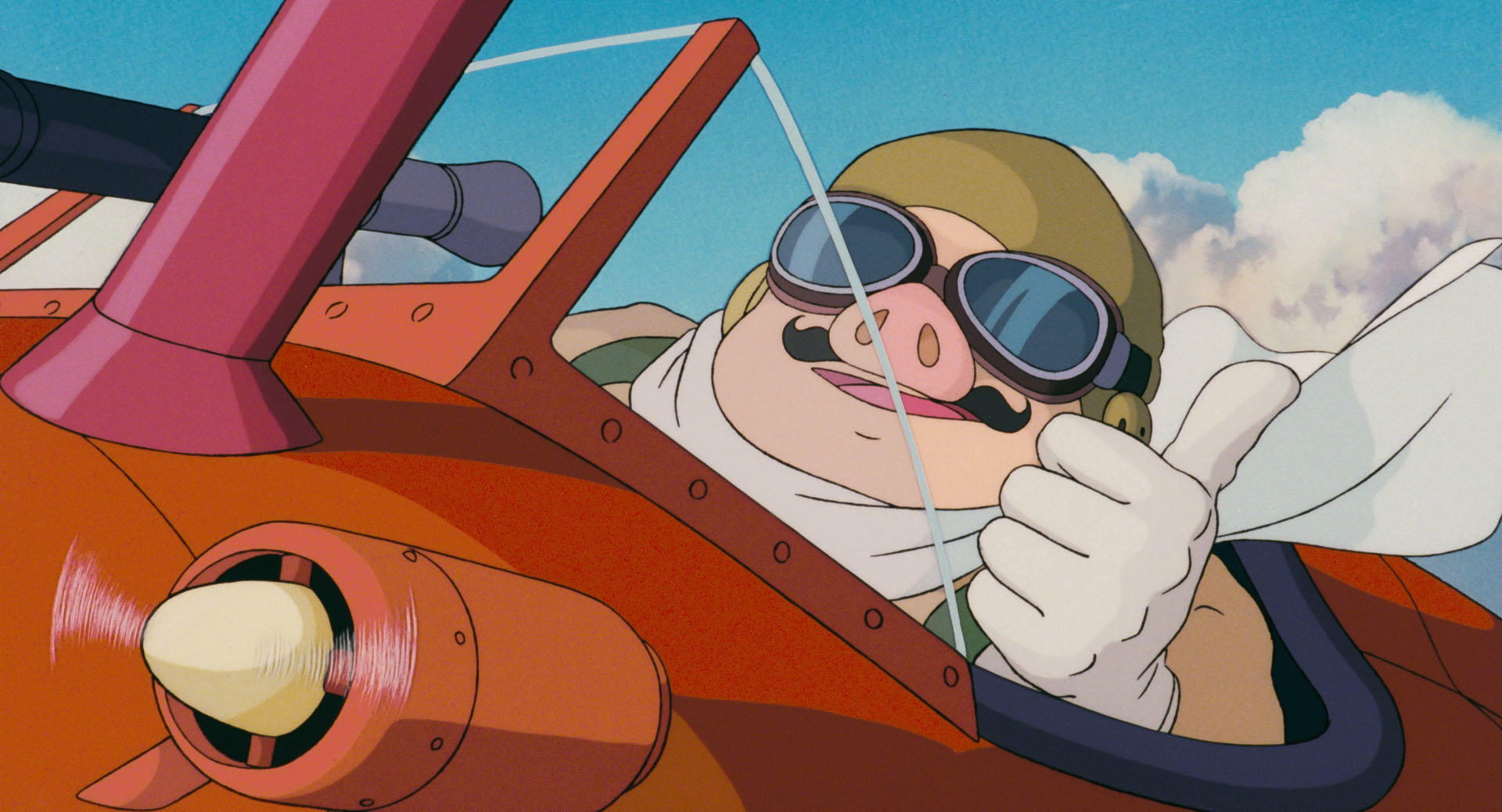

The abundance of planes and other aircraft was made even more centre stage with Miyazaki’s next film, 1992’s Porco Rosso, meaning Crimson Pig. The film saw a First World War fighter pilot turned literal pig face off against the fascist Italian air force of 1929. Despite being much more overtly political than Miyazaki’s other films it still has the mass appeal that is seen with his other forays, with the characters being likeable and the action being intense, particularly during the films many dogfights.

Moreover, the screenplay of the film is commendable, containing some of the best lines in all of Miyazaki’s filmography, particularly “I’d rather be a pig than a fascist”. As expected, the film explores many of Miyazaki’s anti-war sentiments, particularly his distaste for more authoritarian political stances.

Princess Mononoke released in 1997 to universal acclaim. It is cited as one of Miyazaki’s most well-crafted and narratively brilliant pictures, having deep thematic throughlines on the evils of war and over-industrialisation and the necessity of nature to providing hope and life for humanity. In this regard it can be viewed as a spiritual successor to Miyazaki’s previous work on Valley of the Wind in 1984, touching on many of the same ideas and themes as that film did but with the directors nearly 15 years of experience and expertise shining through to improve upon his original work in nearly every aspect. On top of these it also touches on aspects rarely seen in Miyazaki’s other films, namely the ideas of sexuality and disability, both of which inspired by the experiences of those that Miyazaki had met during the development of this film.

This film features some of Miyazaki’s most fascinating and enticing worldbuilding, with the more spiritual elements being incredible in execution and brilliant in concept and design. It is also notable for its record-breaking elements, topping the Japanese Box Office at the time of its release to become the all-time highest grossing film in the country with an earning of ¥20.18 billion, only being surpassed by James Cameron’s Titanic a few months later. Princess Mononoke is remembered today as one of Miyazaki’s greatest films, and one of the greatest animated films of all time for its more mature themes and content and the overall quality of the film.

Spirited Away has become symbolic of Miyazaki’s filmography and is easily the film he will most fondly be remembered for in history

Being a successor to one of his greatest films, Miyazaki’s next would have a lot to live up to, and in every regard, it succeeded. 2001 saw the release of Spirited Away, often toted as being Miyazaki’s magnus opus. This film is regarded by many as the greatest animated film of all time, the title of which is not unearned. Through the film, Miyazaki creates an almost indescribable atmosphere that is perfect in both its intentional unease and its creative whimsy, crafting a world that is defining of Miyazaki’s style for its influences from spiritual myth and its application of this otherworldly aesthetic in telling stories that are some of the most conducive to the human experience seen in cinema. The story of Spirited Away is one that largely focuses on identity and with this the importance of love to defining both the idea of self and humanity.

Arguably, this film is a contender for being the best demonstration of the power of love in Miyazaki’s repertoire, an accomplishment considering how frequently the idea appears. This film contains more of Miyazaki’s most memorable and frequently occurring iconography, particularly the character of No-Face, who is a completely original design by Miyazaki with no basis in spirituality. No-Face is a design that has reoccurred in pop-culture since his inception in 2001 and alongside Totoro is exemplary to Miyazaki’s lasting impact as a director.

Spirited Away, even 20 years after its initial release, is a film that is still regarded as being masterfully constructed in every aspect and is seen as a classic of not only Japanese cinema, but also the animation industry – surpassing Disney’s entire catalogue regarding quality – and cinema as a whole, being cited by many as being in the 10 greatest films of all time. Because of this, Spirited Away has become symbolic of Miyazaki’s filmography and is easily the film he will most fondly be remembered for in history.

2004 saw the release of Miyazaki’s next film: Howl’s Moving Castle. Loosely based on the English novel of the same name, Miyazaki uses the film as to further convey his ideas of love, compassion and the destructive nature of war. War is an ever-looming presence throughout the films runtime, with it effectively being the main antagonist of the film – it is ever present in the background of the film and has a constant agency over the characters and events of the plot. Despite this though, through Miyazaki’s desire to show the positive impacts of love and life, he manages to make the film positive and heart-warming for viewers, especially in his exploration of how compassion can help overcome said conflicts. In 2013 Miyazaki said that Howl’s Moving Castle was his personal favourite of all his films stating, “I wanted to convey the message that life is worth living, and I don’t think that’s changed.”

Ponyo on the Cliff by the Sea, better known as just Ponyo, was Miyazaki’s next film. Releasing in 2008 and being an adaptation of The Little Mermaid, Ponyo is a film that explores love in a deeper aspect than any of his previous films. Within the film, all characters are motivated by a love of some description: platonic, romantic and familial love are all motivators within the plot. Miyazaki’s passion for life in even the simplest of forms continues to shine through remarkably with this film, being an excellent addition to his filmography.

Ponyo is also notable in Miyazaki’s history for how well it performed outside of Japan upon its release. Thanks in part to having the least time between its domestic and international release and opening in 927 cinemas across the US and Canada, a much wider release than previous Studio Ghibli films. Ponyo had by far the largest international gross at the international box office out of all of Miyazaki’s films to that point.

The Wind Rises can be seen as the work most symbolic of Miyazaki’s entire career

Miyazaki’s current latest film, The Wind Rises, was released in 2013 and was intended to be his final film before his retirement. The film is unique in Miyazaki’s repertoire in that it is a semi-fictious account of the life of Jiro Horikoshi, an aviation engineer during World War Two. The Wind Rises is remarkable for how it is a very clear and definitive conclusion to the ideas and themes that Miyazaki has presented in his 10 previous works beforehand. The film is explicitly anti-war, in particular with its negative depiction of the Japanese and German militaries during the Second World War. Its exploration of love and the often-fleeting beauty of it is a particularly touching element that Miyazaki expertly weaves into the narrative with a level of care that could only be achieved with his level of experience. Most notable in its conclusiveness to the typical elements of Miyazaki’s storytelling is its exploration of aviation.

With aircraft being an almost omnipresent element of Miyazaki’s films to the point where they are almost symbiotic with one another, it is his work with The Wind Rises that finally gives a justification to their heavy inclusion over his then 33 years of work. Within The Wind Rises aircraft are symbolic of the beauty of life and how this beauty can truly come from anywhere – even within the atrocities of the Second World War beauty was still able to be found in the form of the aeronautical engineering feats of the time. The Wind Rises can be seen as the work most symbolic of Miyazaki’s entire career – it encapsulates his visions and struggles as an artist, as well as being a natural and well earnt finale to the many ideas that he explored in his 33 years as a director.

Finally, the character of Caproni is a stand-in for Miyazaki in many ways, subtly guiding Jiro (the audience) throughout the film even if he may no longer be there in reality. The Wind Rises acts as Miyazaki’s goodbye to his audience and is a heartfelt and touching conclusion to his work.

Miyazaki’s retirement lasted for 3 years, returning to Studio Ghibli in 2016 to begin his work on How Do You Live?, planned to be his final work. The film is currently 6 years into production and said to be progressing well according to those at the studio. His reason for coming out of retirement is wanting to make a film for his grandson as to explain “Grandpa is moving onto the next world soon, but he is leaving behind this film”.

Miyazaki is in no way short of being a truly phenomenal director. With a filmography unlike any other, he is a master of his craft being one of, if not, the best director of all time. From his attention to detail in the quality of his animation to the exploration of ideas, themes, and plotlines that he is passionate about and explains with an unrivalled care, he is a director who values the quality of his work and what it has to say above all else. His impact on popular media and his role in almost single-handedly making Japanese cinema mainstream for western audiences are to be commended, and alongside his brilliance as a filmmaker ensure that he will be fondly remembered and his films rewatched for years to come.

For more Director Rundowns, check out these articles from Redbrick Film:

Godard Obituary – Novelle Vague Giant Who Transformed Cinema Dead At 91

Comments