Comment Writer Danielle Murinas considers the A-Level results day fiasco and what it tells us about the British class system

A-Level results day is an understandably daunting prospect, occurring annually in mid-August. But this year, it became a national disgrace, highlighting the ongoing elitism that still underpins British society.

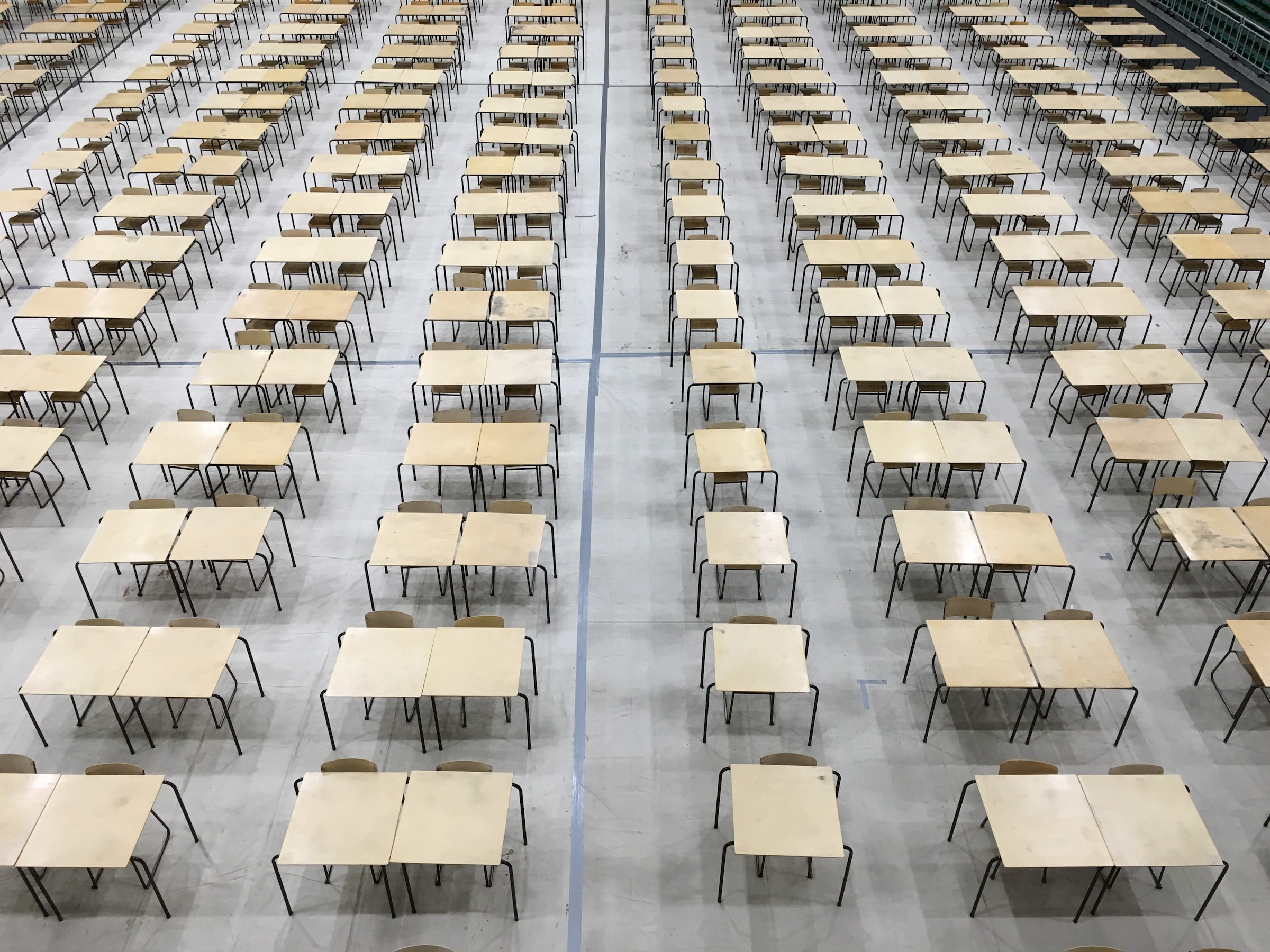

The coronavirus pandemic meant schools were forced to close back in March, and with concerns over safety, exams were cancelled, meaning thousands of A-Level students in England were unable to complete their assessments. This meant that the way students’ grades were awarded had to be severely modified. Ofqual worked with government ministers on an algorithm that would allocate individual students their final A-Level grade. Ofqual believed teachers would be overly generous when giving out results, so used the algorithm to counteract this. However, the algorithm proved to be highly ineffective, and caused outrage across England.

A staggering 40% of students had their results downgraded from figures their teachers had predicted them. A total of 280,000 students were given lower results than expected, and ones which did not reflect work completed throughout the year. Many flocked to Twitter to express their shock and disappointed in their end results. One particular viral tweet brought to light a young woman who was predicted A*A*A, and achieved AAA in her mocks being award BBC, while other replies discuss being downgraded from A*A*A to DDC.

The immediate shocked and angry reaction is understandable, especially as it transpired that working-class students were more likely to be downgraded, as the algorithm recognised them as being from a deprived area, where students previously received lower grades. Meanwhile, there was an increase in A* and A grades disproportionately given to students in independent schools rather than state schools, with 49% of privately educated students receiving an A grade or higher, compared to 20% of state-educated students. Although students attending such private schools undoubtedly worked hard to achieve their grades, so did the thousands of individuals in state schools who were unfairly treated simply because of their socio-economic circumstance.

Although students attending such private schools undoubtedly worked hard to achieve their grades, so did the thousands of individuals in state schools who were unfairly treated simply because of their socio-economic circumstance

What this scandal does emphasise is that classism and elitism are still core aspects of British society, and can be used to govern British policy. It would be easy to assume that classism no longer plays a part in society, in comparison to historic periods where societal power belonged to the aristocracy and the middle class. But although this landscape has changed, Britain does still have an innate class system, in which socio-economic background can unfairly disadvantage you from a young age. The A-Level fiasco is simply one example in how classism can be inadvertently weaponised against working-class people.

The matter of classism within education also relates to more long-standing discussions about the elitism of top universities when it comes to applicants. Oxbridge, for example, still has a disproportionate number of students from the top one hundred schools in England. With another report concluding that over 60% of Oxford students originate from private or grammar schools, and only one in ten would consider themselves working-class. Although outreach initiatives have been developed in order to make these institutions more inclusive, it will likely be a painfully slow process as the matter of elitism is more deep-rooted than one might hope.

Attending a privately educated school not only affects people’s academic career, but also job opportunities that are open to them. A 2019 government report showed how the most influential people in the country were more likely to have been privately educated. Despite only seven per cent of the population in England attending private schools, 39% of people in top positions attended such institutions. 52% of senior judges, for example, are alumni of private school and then Oxbridge. Although individuals would have all worked hard to achieve this, it does enlighten us how class can underpin opportunities into different career paths. Therefore, an education based on elitism has repercussions that can last for an individual’s lifetime, and which will consequently have an impact on the rest of society.

Education based on elitism has repercussions that can last for an individual’s lifetime

Finally, it does lead one to question what steps will be taken to eliminate such elitism from society. The A-Level algorithm was abandoned after a national outcry, in a governmental U-turn. But given Boris Johnson’s promise to give all students a ‘superb education’ with increased school funding – which would level up the lower funded North and Midlands – it does provide an incoherent message on behalf of the Conservative government. Despite these words, their initial actions show a government who are not concerned with eliminating classism, but instead allowing it to govern policy, instead of actively trying to discourage it. Hopefully, the Conservative government will have learnt from this scandal, and not allow socio-economic backgrounds to govern any similar decisions.

Related articles from Comment:

How COVID-19 Deepened Educational Inequality

A Results Day that Let Down the Poor: Grading Students by Their Postcode

The Government’s Decision to Make GCSE Poetry Optional for a Year is a Slippery Slope

Comments