Comment Writer Colette Fountain discusses the lack of female protagonists in children’s literature and, in particular, the influence of Jacqueline Wilson’s novels

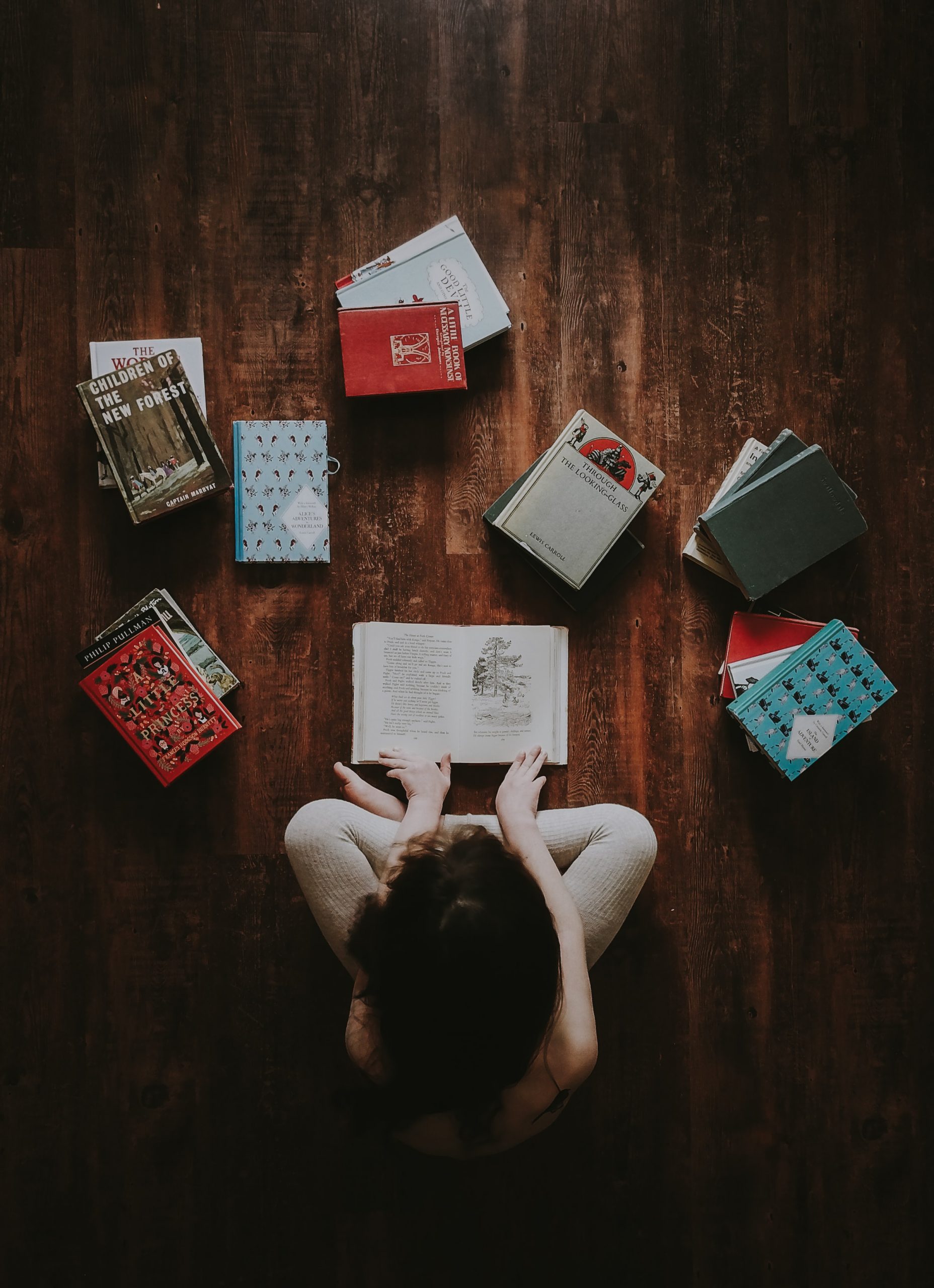

Publisher James Dashwood tells Jo March at the beginning of Greta Gerwig’s adaptation of Little Women that ‘if the main character’s a girl, make sure she’s married by the end. Or dead, either way.’ While this might seem like a particularly cynical depiction of the ways women are represented in literature, in many ways female protagonists are still restricted by these tropes, even over 150 years after Louisa May Alcott’s novel was published. As an avid reader and literature student, I like to think I have been exposed to a variety of genres, however, many of these novels simply lack female representation or, if the protagonist is a woman, perpetuate the sexist undertones identified by Gerwig.

Like most creative disciplines, English literature disproportionately favours male protagonists. A study found that in children’s literature, 68% of books feature a male protagonist in comparison to 19% which have a female lead; preparing children for a world of literature that remains skewed towards men. In my entire academic career, I think I would be able to count on one hand the number of books I have read that have female protagonists, limited to books like Pride and Prejudice and Mrs. Dalloway. In contrast, I have read a seemingly endless collection of books starring a male protagonist, from Jekyll and Hyde to Robinson Crusoe. This not only highlights the vast gender gap in terms of character choices but also raises issues regarding the portrayal of these genders. While Austen’s novel could be argued to subvert gender roles through the protagonist Elizabeth Bennett, ultimately all of the Bennett sisters are married by the end. Obviously, Austen’s novel alone isn’t the issue – after all 50% of women are married by 28 so it remains a relatable novel – but issues arise when this is the only narrative being told, one where women’s only struggles in life seem to be choosing between love interests.

English literature disproportionately favours male protagonists

Someone who consistently subverts the norms of female protagonists is Jacqueline Wilson. I absolutely adored her work and, although I did not realise it at the time, she is probably responsible for shaping a significant part of my childhood. Again, at the time I did not realise that the way she portrayed women in literature was anything revolutionary, but looking back I struggle to find books, particularly for children, that cast such a diverse range of women as their protagonists. Wilson’s novels almost always focused on a fiercely independent teenage girl who rarely had time for boys, and if they did, this usually ended badly, subverting the typical ‘fairytale ending’ of women’s literature. Her novels were never sugar-coated, instead portraying the harsh realities of life from abandonment, to teenage pregnancy to volatile households. While some people may feel this is not appropriate for children, I always felt that unlike some authors, Wilson never patronised her audience: for many children these were issues they were already struggling with and it might help to have someone address it in literature. Female protagonists in literature seem to be torn between two very different paths – either the conventional marriage/romance plot or having to have a tragic backstory and home life, creating the idea that the average woman is not worth talking about. While there are hundreds of novels and films about average, everyday men, very rarely is there something depicting the average life of women. Instead, they have to be particularly tragic or in love in order to be deemed worthy or important enough to be written about, something that does not apply with male protagonists.

Female protagonists in literature seem to be torn between two very different paths – either the conventional marriage/romance plot or having to have a tragic backstory and home life

Once I grew out of my Jacqueline Wilson faze and shifted towards young adult literature, I managed to find more female protagonists in trilogies like The Hunger Games, Divergent, and John Green’s novels. Katniss Everdeen was everything I wanted to be at the time: strong, independent, brave, building on the strong female role models Wilson had introduced me to. And yet, despite the power that characters like Katniss Everdeen held as individuals, there still always seems to be a need to revert to at least some variation of the marriage plot, perpetuating the idea that women are incomplete without a man. Despite everything that Katniss goes through, the over-arching storyline is still her decision between Gale or Peeta, something that she believes ultimately boils down to who she cannot survive without. The novel’s epilogue ends with (spoiler alert), her marriage to Peeta as their two children play in the field, perhaps proving that all along, her choice in men was the most important aspect to the plot. Similarly, many of John Green’s novels focus on the love lives of their female protagonists, as does the Divergent series which, despite the intense conflict, focuses largely on Tris’ relationship with Four. Again, while this alone is not problematic, it perpetuates the idea that women cannot exist as a protagonist unless they have some relation to men.

This is not intended to be a critique of authors – Jacqueline Wilson and Suzanne Collins will always have a special place in my heart, and their novels helped shape who I am today. I also cannot deny the influence that their female protagonists had on me: in a time where, academically, I was reading novels led by men, I managed to find brave, independent female role models. The issue, therefore, is more widespread. Men seem to be less likely to read novels with a female protagonist as they potentially struggle to relate, while women seem to have a greater ability to relate to novels led by men as we have had to adapt to the male-dominated world of literature. Addressing the reasons why men struggle to relate to female protagonists is a good place to start, as is trying to undo some of the beliefs that women are only worth reading about if they have something significant to say about society, end up married, or dead.

_________________________________________________________________________

Like this story? See below for more from Comment:

Should I Stay or Should I Go? Two Sixth Formers on Starting University in September

Comments