In an exclusive article, Gaming Writer Daniel Bray and Editor Sam Nason give their arguments for and against whether exclusivity has been good for the video games industry

‘[Exclusivity means] better games, and better consoles – meaning a better gaming experience for us all’ – Daniel Bray

The use of games exclusivity is important in the gaming industry as they allow for increased competition, the opportunity to focus on clean, polished games, and a higher potential for innovation in the industry.

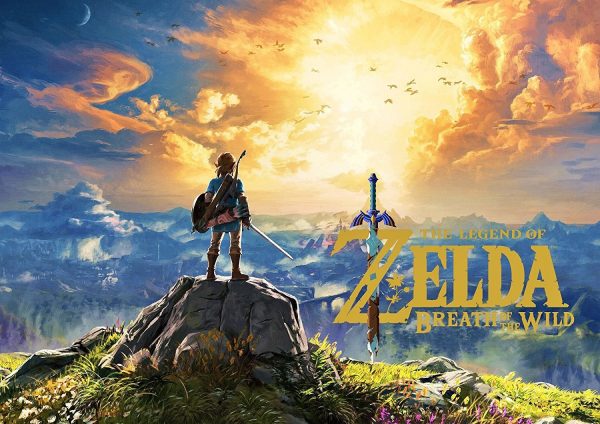

Nintendo’s Wii U console was a disaster by most metrics – it’s the lowest-selling home console Nintendo have ever created. Without the strong library of exclusives that Nintendo has to offer – including the Mario, Smash Bros. and Legend of Zelda franchises – it’s not inconceivable to think that Nintendo could’ve lost their last life. But instead, they carried on and produced the Switch – a resounding success of a console, which has really shaken up the console industry, blurring the lines between handheld and home console.

If we take another look at Nintendo, we can understand one of the more subtle points regarding video game exclusives. First, we must go back to 1988; a few years after Nintendo launched the NES in North America. At this time, Electronic Arts were looking to release titles on Nintendo’s system. But the terms of Nintendo’s licensing agreement – including the fact that they wouldn’t say whether they would sell your game until development was completely finished, and a 2-year exclusivity deal – were so unbelievably one-sided that EA decided to take their business elsewhere. This led EA to Sega, who had just released their Genesis console. This time, they took to the negotiating table in search of a more favourable deal, but to EA’s disbelief, Sega refused to be pushed around, demanding the same terms as Nintendo.

As a result of this setback, EA put their two most talented engineers to work, in an attempt to reverse engineer the Genesis. Fast-forward to a few months later and they’d figured it out. They were preparing to release their own Genesis game cartridges at CES – the biggest convention for developers at the time. EA were kind enough to alert Sega about their success before the big reveal, and so Sega begrudgingly fleshed out a deal with EA to prevent the sale of EA ‘bootleg’ Genesis development kits. The bigger picture of this ordeal with EA – now everyone’s favourite microtransaction provider – is that it forced Sega to soften its position on licensing terms, therefore attracting more developers to create games for them rather than Nintendo. This competition for exclusivity produced a positive impact towards developers who, as a result, were being treated more fairly by the big behemoths of the hardware world – which, from all angles, is a good change.

This competition for exclusivity produced a positive impact towards developers who, as a result, were being treated more fairly…

Let’s shift focus to the two ‘big players’ when it comes to home consoles; Microsoft and Sony. The number of PS4 exclusives is almost double that of the Xbox One, despite the Xbox One X having better Specs than the PS4 Pro. I would argue that there is a balance created by these two factors – the larger library of PlayStation exclusives allows Sony the chance to improve their hardware to compete with the Xbox, whereas the superiority of the Xbox’s hardware allows them some leeway while they try and get their collection of exclusives up to scratch. The result of this? Better games, and better consoles – meaning a better gaming experience for us all, from enthusiasts to casual players.

‘…it is purely as a result of monetary greed that overlooks the consumer’ – Sam Nason

Exclusivity has been a key – perhaps even necessary – factor to the development of the video game industry as we recognise it today. But in an increasingly connected landscape with games becoming more and more difficult to keep track of and preserve, has this practise gone too far?

Understand that when I talk about exclusivity here, I’m talking about it in a more specific sense, where games or downloadable content that could feasibly be pushed to other platformers is prevented from doing so by their publishers.

The recent controversy surrounding Call of Duty: Modern Warfare is a prime example of this. Revealed in Sony’s latest State of Play presentation, the Survival mode for the game, a horde-based spinoff of the Spec Ops missions, will be exclusive to the PS4 for an entire year. This essentially damns the mode to obscurity for PC and XBOX users as, by the time the mode becomes available to them come October 2020, it will be marked as irrelevant due to the looming of the next entry in the franchise.

With consoles becoming closer in terms of connectivity – think Nintendo and Microsoft with their Play Together campaign, or the recent cross-play between Sony and Microsoft with PUBG – the concept of ‘exclusivity’ becomes a rather archaic practise that appears more hostile than helpful.

Arguably, Microsoft have acted as pioneers over the past few years with their efforts to collaborate with other companies – rather ironic given their past greedy practises. With Ori and the Blind Forest – a game I feel “few platformers […] have captured the charm, heart and warmth of” – and Cuphead jumping to Switch and Game Pass games connecting across XBOX and PC, Microsoft have emerged as a figurehead for a sort of kinship between consoles, transcending ‘console wars’ and instead celebrating games and their players.

Exclusivity, after all, creates an unnecessary division whereby a large portion of the gaming community are denied the opportunity to experience a title. To give examples, consoles that were less financially successful like the Wii U or the Sega Dreamcast have games fade into obscurity as they are doomed to suffer the same fate as the console that platformed them. A lack of game preservation is a bi-product of exclusivity and, in some cases, causes games to be lost in corners of history that are difficult to find again.

PC emerges as an example of non-exclusivity; broader player bases, a wide selection and variety as well as an impressive indie and fan-game community show a platform that unifies rather than divides. Ironically however even this appears to be coming (semi-)under fire with Epic Games and Steam battling it out for the rights to certain titles.

As amends appear to be made, other breakdowns begin to occur. As stated at the beginning, perhaps exclusivity is a necessary practise for competition and innovation. But that doesn’t mean it’s ideal for consumers.

Comments